Border Inequalities

Nestling between the Velebit massif and Mount Dinara, which forms the border between Croatia and Bosnia, the Croatian Lika region reveals its high karst plateaux in the muted light of spring. Honey and cheese stalls alternate with herds of racy cows and horses. There's also a bear sanctuary where nature-loving volunteers from France and Austria try their hand, alongside tourists from all over the world who flock to visit the famous Plitvice Waterfalls and Lakes National Park, a world-renowned UNESCO World Heritage Site welcoming over a million visitors every year. Only the many ruined farms give the landscape a sombre note, reminding us that it was on this stretch of the border that one of the fiercest episodes of the Serbo-Croat war was played out, from 1991 to 1995. In the calm that has returned, who could suspect that these high mountains are still the scene of violent and sometimes deadly hand-to-hand combat?

My gaze lingers on the Dinara and I set off along the banks of the Korana River. The number of Croatian border police vehicles increases as I head towards Bosnia-Herzegovina, as do the checks. Near Plitvice Park, the police simply check the identity of travellers and ask them where they are going. Names are sometimes written down on a piece of paper to keep track of people and vehicles that have already been checked: border controls must not get in the way of this early tourist season.

The Lika plateau towards Plitvice and Bihać, April 2024. Photo: Morgane Dujmovic

I make my way up the mountain, approaching the pass that marks the border at Ličko Petrovo Selo (Croatia) / Izačić (Bosnia and Herzegovina). Here, the border police vans cross each other with greater intensity, some stationary, others on duty. A policeman patrols one of the countless derelict buildings – the property of the Serb populations who lived there before the military Operation Storm to reconquer the Krajina. Through the openings in the collapsed walls, I can already guess that some of today's exiles might be taking refuge there. But the effects of the sordid cat-and-mouse game that takes place at nightfall are only felt once the mountain pass has been crossed, on the Bosnian side.

The game is the cynical name given over the last few years to the constantly reinvented attempts to cross borders and join the European Union (EU). The Bosnian canton of Una-Sana has become one of the theaters of this game since the closure of the formalized Balkan corridor in 2015-2016 (Bužinkić and Hameršak 2018; Dujmovic 2016; Dujmovic 2019; Bacon 2022). Located in the extreme north-west of Bosnia, this region represents one of the most direct routes from the southern Balkans to the Schengen area. From 2017 onwards, with the reinforcement of the Serbian-Hungarian and Serbian-Croatian borders, exiles on the Balkan routes were more clearly oriented towards Una Sana, from where they could hope to reach Slovenia, about one hundred kilometres away.

Since Croatia joined the Schengen area on January 1, 2023, land and sea controls have been lifted with Slovenia, Hungary and Italy, while airport controls were eased on March 26. This theoretical free movement area is just on the other side of the mountain that can be seen from Bihać, the administrative centre of the canton.

Over the last twenty years, Croatia's application to join the EU and then Schengen implied a drastic increase in the resources allocated to fortifying the Bosnian-Croatian border, in terms of human, technological and financial resources (Dujmovic 2019). On the Bosnian side, the regions bordering Croatia have thus become one of the priority areas for migration control upstream of Schengen: the EU deploys devices to consolidate a filtering buffer-zone, designed to separate the wheat from the chaff – i.e. migration deemed acceptable from that deemed undesirable. This filtering function has been applied to the entire Balkan peninsula since the 2000s, as shown in 2015 the map “The Balkan buffer-zone” (Dujmovic 2015). This process of externalization is exerted under constant political and financial pressure in the context of Bosnia-Herzegovina's application to join the EU – whose candidate status was confirmed by the European Council in December 2022, almost seven years after the Bosnian authorities applied for membership, on February 15, 2016.

In the canton of Una-Sana, the “buffer-zone” function attributed to Bosnia-Herzegovina is based on the specific geography of the region: this semi-enclave in the shape of a pocket forms a veritable bottleneck for people whose journey is stopped there. This strategic use of space is comparable to what was observed as early as 2015 in the Roya Valley (see the map “Vallée de la Roya: un terrain de chasse meurtrier dans l'espace Schengen” by Morgane Dujmovic and Thibauld Duffey 2017). As can be seen at other EU borders that are kept closed, in Bihać it is common to see groups walking along the road for the fifteen kilometres that separate the town from the border crossing point of Izačić, either because they've just been turned back by the Croatian police, or because they're heading for the border to try a new game.

Izačić, towards the Croatian border point visible in the background, April 2024. Photo: Morgane Dujmovic

In the town of Bihać, residents have been witnessing repressive strategies to push these exiles out of Croatia and fix them in the canton for seven years now. The high point was reached in 2018, in terms of border crossings and violence: according to figures compiled by IOM in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the level of detected entries was 24,067 in 2018, 30 times higher than the previous year (755 in 2017). A shopkeeper in Bihać recalls in a conversation in April 2024:

Until Covid, it was really tough, as people were sleeping all over the place around the town, in the forest, in places that weren't suitable at all. We saw a lot of people from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kurds, blacks from African countries too, and often families with very young children. We ourselves can only understand people fleeing countries at war or having to live in camps: we lived through the war, four years of siege in Bihać.

The rhetoric of openness and compassion intersects with local discontent: the discontent, for example, that led to the closure in October 2020 of the Bira camp, which until then had been located in the centre of Bihać. At the height of the management of the Covid-19 pandemic, some of the people housed there were transferred to another camp located 27 kilometres from the town, in a remote rural environment well away from the Croatian border (Fernier 2022: 4-5). In spring 2024, this was the only official accommodation for single men: only families and minors were accepted in the city, in the Borići camp known among exiles as “the family camp”. The transformation of this former student residence into a camp has mobilised a European budget of one million euros, both for its reconstruction and its operation since 2018, according to the figures provided by the EU delegation in Bosnia-Herzegovina for the inauguration of the building's final facade works in July 2022.

Borići Family camp in Bihać, May 2024. Photo: Morgane Dujmovic

The Borići camp is planted in a pine forest that gives it its name (borova šuma, in Bosnian) and its facade was refurbished in the summer of 2022; this peaceful atmosphere almost makes forget the anxiety that is replayed every day for the people housed there. Although categorised as “vulnerable” by humanitarian institutions and organisations, these isolated women, families and children are subjected to violent refoulement every time they make an abortive attempt to cross the mountains into Croatia. For those who have already tried the crossing, the camp is a place of eternal flashbacks, a temporary but fragile respite, as the senses are entirely turned towards the prospect of a new attempt. One of the families I met there had a member recovering from an injury sustained on the Balkan routes; for them the time for crossing the border had not come, “not tonight”.

“Not tonight”, facing the mountains towards Croatia, May 2024. Photo: Morgane Dujmovic

I set off again in the direction of the Lipa camp. Along the banks of the river Una, the tourist signs are a reminder that this region which is synonymous with dull anxiety for some, is a place of discovery and fun for others. In the Una national park, as on the Croatian side, private apartmani are filling up for “the season”, while the first groups of tourists are revelling in the spring atmosphere at the water sports sites and waterfalls.

Within the Bosnian Ministry of Security, the Service for Foreigner's Affairs (SPS/SFA) has clearly stated its intention to reconcile this freedom of movement with European standards of migration control. In recent years, Bihać and the canton of Una-Sana have thus become one of the many border areas in the world where a “bipolar differentiation” is taking shape (Sassen 2010), between the world of desired, tourist and profitable migration, and that of undesirable migration, made up essentially of people from the Middle East, Asia and Africa fleeing violence, war, persecution or untenable socio-economic situations.

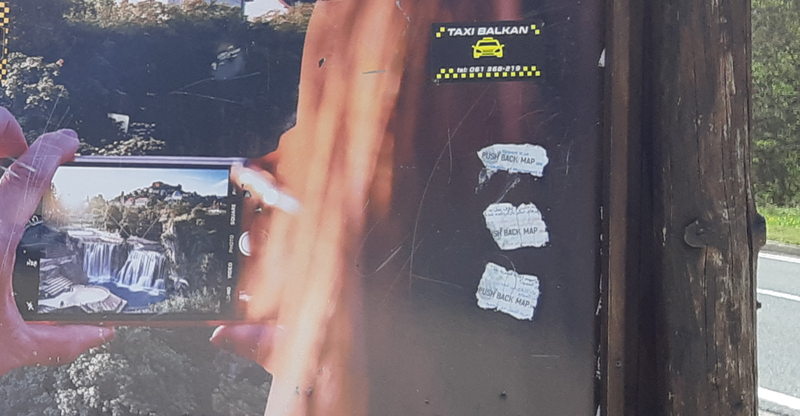

A few subtle signs of these profound inequalities in mobility stand out in the idyllic landscape... At the last junction leading to the Lipa camp, on the roadside tourist signage, stickers indicate the omnipresence of taxis and the existence of a pushback map.

Tourist signs along the access road to the Lipa camp, April 2024. Photo: Morgane Dujmovic

Tourist signage, details, April 2024, Morgane Dujmovic

18/9/2025

This text is taken from the series of portfolio articles “Rivers are deadly if you're not on the right side” previously published on Mediapart, Le Courrier des Balkans, visioncarto.net and Migreurop. This series of portfolio articles is the result of field research carried out in the spring of 2024 in several South-East European countries: Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro and Albania. This publication is sent to all interlocutors met in the field. To preserve their anonymity, the exiled people are referred to here by a randomly assigned letter, with their consent.

The author would like to thank the exiled people she met on these roads and along these rivers, the people from the collectives, associations, universities and institutions with whom she spoke, as well as Louis Fernier, Romain Kosellek, Eva Ottavy, Elsa Putelat and Marijana Hameršak for their invaluable contributions prior to and during this field mission.

Literature

Bacon, Lucie. 2022. La fabrique du parcours migratoire sur la route des Balkans. Co-construction des récits et écritures (carto)graphiques. PhD Dissertation. Université de Poitiers.

Bužinkić, Emina and Marijana Hameršak, eds. 2018. Formation and Disintegration of the Balkan Refugee Corridor: Camps, Routes and Borders in the Croatian Context. Zagreb: Zagreb and Munich: Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research, Centre for Peace Studies, Faculty of Political Science University of Zagreb – Centre for Ethnicity, Citizenship and Migration, bordermonitoring.eu e.V.

Dujmovic, Morgane. 2015. “The Balkan buffer-zone”. Migreurop/closethecamps.org

Dujmovic, Morgane. 2016. “Balkans, du corridor au cul-de-sac”. Plein droit 111/4: 23-26.

Dujmovic, Morgane. 2019. Une géographie sociale critique du contrôle migratoire en Croatie: ancrages et mirages d'un dispositif”. PhD Dissertation. Aix-Marseille Univ.

Dujmovic, Morgane. 2017. “Vallée de la Roya: un terrain de chasse meurtrier dans l'espace Schengen”. In Migreurop. Atlas des migrants en Europe. Approches critiques des politiques migratoires. Paris: Armand Colin.

Fernier, Louis. 2022. Camp de réfugié-e-s de Lipa. Paris: Observatoire des Camps de Réfugié-e-s.

Sassen, Saskia. 2010. “Villes entre vieilles frontières et nouvelles clôtures du capital”. Multitudes 4/43: 50-59.