Schengen

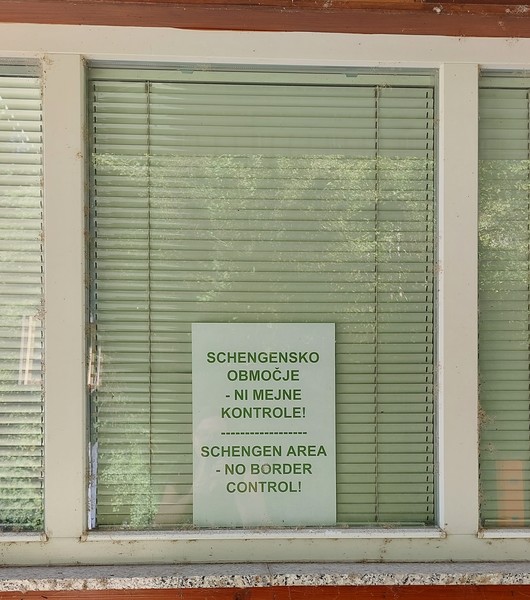

Schengen is the name for the project of abolishing border controls between the central European states and introducing enhanced border controls on the European periphery. It is used as a spatial metonymy for the Schengen acquis and related documents, systems, and practices: Schengen Agreement, Convention Implementing the Schengen Agreement, Schengen Borders Code, the Schengen Information System (SIS), the area it covers, short-stay visas, and more. In addition to this official, legally defined terminology, unofficial terms such as the Schengen Area, Schengen visa, Schengen border, Schengen instrument, or Schengen state are also circulated in the media and everyday speech. The EU terminological database IATE contains other less known terms, such as Schengen ID, Schengen alert, Schengen cycle, and even Schengen bus.

Schengen terms in the form of negations are particularly interesting, such as the term non-Schengen visa, which was informally used for visas for EU countries that were not to a part of the Schengen Area (Romania, Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Croatia). Besides, some terms intentionally mobilize the Schengen imaginary, as a brand that guarantees the establishment of respected regulation and evaluation systems (origin and quality of goods and finances, compliance with standards, or people’s identity) and control of movement. One such term is small or mini Schengen, which was used to name the alliance of Western Balkan states that, as quirk of fate, were themselves listed on the so-called Black Schengen or Black Schengen list not so long ago. The latter is another Schengen term referring to the list of countries whose citizens need visas to enter the Schengen Area in the 2000s.

Schengen owes its name to the village where in 1985 Germany (then West Germany, or the Federal Republic of Germany), France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and the Netherlands signed an agreement to gradually abolish border controls at their borders. The agreement was actually signed on the boat Princesse Marie-Astrid, near Schengen, on the section of the Moselle River that is at the tripoint of Germany, Luxembourg, and France, a location of distinct symbolism for the new “post-national” approach to border control (Zaiotti 2011: 4). Schengen originated outside the framework of the European Union, then the European Economic Community, into which it was subsequently implemented during the 1990s and 2000s through treaties, agreements, and meetings, sometimes also named after geographical locations, such as as Treaty of Amsterdam or Treaty of Lisbon.

The implementation of Schengen into the EU, which was one of its goals from the beginning, was accompanied by debates and disputes, but also with the Schengenization of the Union, instead of the expected Europeanization of Schengen (Zaiotti 2011: 153). As a model established multilaterally and from the top down, bypassing mechanisms of democratic control, a posteriori and basically in a fluid and non-binding way included in the EU (Votoupalová 2020), Schengen continuously spills over its own physical and legal boundaries, simultaneously ensuring and perpetually threatening the cultural, political, and spatial coherence of the EU. One of the results of the subsequent implementation of Schengen into the European Union is that the EU, as William Walters noted in the early days of Schengen (2002: 567), does not have a single border that can be said to define a unified administrative space.

The Schengen Area, which is currently several times larger than it was in 1995, when the first seven European countries began implementing the agreement to abolish border controls, still does not encompass all EU member states, while it includes several non-EU countries. Furthermore, Schengen covers areas of its influence, or more precisely, areas dependent on it. In line with the externalization tendency of Schengen as an EU internal externalization project along the center-periphery line (Cobarrubias et al. 2023), Schengen mechanisms are applied outside the Schengen Area of free movement. Parts of the Schengen acquis, finances, and practices spill over into non-Schengen EU countries through prolonged, almost neverending accession processes to Schengen, as was the case with Croatia. Schengen mechanisms and methods have recently been increasingly extended to non-EU countries, exemplified by recent agreements between Frontex, the EU and Schengen border guard agency, with North North Macedonia, Albania, and Serbia.

According to Schengen’s logic, strict controls of external borders are a prerequisite for freedom of movement within the Schengen Area, or in other words, the price of abolishing internal borders are tight external-border controls. Schengen in fact amplifies the experience of the border for countries, communities, and individuals at and beyond the external border. Therefore, it is described with metaphors like Fortress Europe and the New Iron Curtain. Furthermore, this logic has generated an increasing focus on joint control of external borders, the establishment and growth of Frontex, and the creation of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), processes that have been loaded with divergent political options, interests, and positions of EU Member States for decades. At the same time, control of internal borders has never really been abolished, but rather relocated inside states through complex and decentralized state and suprastate measures and practices, material, digital, legal, and other systems and tools of movement control, from Eurodac to Dublin and fingerprinting, from public transportation checks near the border, through regular stops at gas stations close to the border, to detention centers, which create “sort of constantly changing and frightening live trap for the undesirables” (Hameršak and Pleše 2018: 9).

The Schengen Area officially has two goals: “Opening up internal borders is one side of the Schengen coin. The other is ensuring the safety of its citizens. This involves tightening and applying uniform criteria on controls on non-Schengen nationals entering the EU at the common external border, developing cooperation between border guards, national police and judicial authorities and using sophisticated information-exchange systems.”The first goal, the abolition of internal borders, which was the driving force behind the entire project and is still a key achievement and symbol of the EU for many of its residents, is now, as this quote shows, reduced to a self-evident and secondary aspect of Schengen, while the second, security aspect, is given much more space (cf. Guild 2001). This conflict between the desire for free, neoliberal, global circulation of goods, services, and capital on the one hand, and biopolitical control of people on the other, is also referred to in the literature as the control dilemma or the double imperative of Schengenland, as Sabine Hess and Bernd Kasparek (2017: 51) remind us. By emphasizing security over freedom, Schengen has, to say the least, a negative impact on neighboring countries and non-EU nationals, states on the external border, the perception and practice of human rights, equality, justice, solidarity, security, sovereignty, and borders in the EU, as already extensively elaborated in academic literature (Votoupalová 2020).

Schengen has often been described in terms of a break with Westphalian borders or as a form of a post-national border that “does not seem to inhabit the terrain of classical geopolitics, of states against states, and of war and peace” (Walters 2002: 564). Schengen borders are more legally defined than physical and fixed to territory. They are inclined towards criminalization of migration (cf. e.g., Guild and Bigo 2010). Therefore, irregular or irregularized migrants have a prominent place in the Schengen landscape. They are “both the alleged ‘cause’ of the need for tougher measures and the performative ‘effect’ of those very measures” (Vaughan-Williams 2015: 20). In other words, in public discourse, Schengen borders are primarily framed as protection from security threats latently personalized in racialized figures of Muslims and non-white people (Walters 2002: 570) who are, moreover, recently militarized through discourses about hybrid warfare, i.e., pressures and interventions by Turkey and Belarus done by sending and directing refugees towards EU borders (cf. İşleyen and Sibel Karadağ 2023). This direction of renationalizing Schengen borders or subordinating them to national interests and imperatives can also be observed within Schengen. Since the long summer of migration 2015, member states have continuously or periodically, often in coordination as in the fall of 2023, introduced border controls at internal borders. These unsystematic controls can be carried out on everyone moving through a certain area (Popescu 2015). In the search for a few migrants, thousands of vehicles are checked. Besides intensifying surveillance over the general population and its movement, these controls also have other consequences, such as the normalization of racial profiling and irregularization in general. The recent wave of introducing controls at internal borders in 2023 had, somewhat like a similar practice in 2015 (Guild et al. 2015), elements of a showcase exercise with extensive media and daily political outreach. Here, Schengen was used strategically, as a tool of foreign policy relations, a means of polarizing voters, spectacularization of borders and the work of border police, and normalizing the perception of migration as a problem.

The spectacle of Schengen controls discursively places the risk beyond Schengen’s borders, while identifying people coming from outside as a disruptive factor. Schengen simultaneously implies that maximum control of those who are already inside (i.e., citizens and residents of states within the Schengen Area) has been established. Foreigners who provide enough relevant data, by biometric passports or documentation submitted for a visa, for example, gain the right to access this area. Since control criteria are met a priori, daily checks within the Schengen Area become redundant. To be able to move within the Schengen Area, people must first agree to surveillance, making “freedom of movement” another rhetorical play of the security regime. Seen from this angle, it is clear that the aforementioned fundamental dilemma or double imperative of the Schengen Area in fact does not exist.

21/11/2023

Literature

Beznec, Barbara, Marc Speer and Marta Stojić Mitrović. 2016. Governing the Balkan Route. Macedonia, Serbia and the European Border Regime. Beograd: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Southeast Europe.

Cabot, Heath. 2012. “The Governance of Things. Documenting Limbo in the Greek Asylum Procedure”. Political and Legal Anthropology Review 35/1: 11-29.

Cobarrubias, Sebastian, Paolo Cuttitta, Maribel Casas-Cortés, Martin Lemberg-Pedersen, Nora El Qadim, Beste İşleyen, Shoshana Fine, Caterina Giusa and Charles Heller. 2023. “Interventions on the Concept of Externalisation in Migration and Border Studies”. Political Geography 105: 102911.

Collinson, Sarah. 1996. “Visa Requirements, Carrier Sanctions, 'Safe Third Countries' and 'Readmission'. The Development of an Asylum 'Buffer Zone' in Europe”. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 21/1: 76-90.

De Genova, Nicholas, Glenda Garelli and Martina Tazzioli. 2018. “Autonomy of Asylum? The Autonomy of Migration Undoing the Refugee Crisis Script”. The South Atlantic Quarterly 117: 239-265.

ECRE. 2022. Country Report. Croatia, https://asylumineurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/AIDA-HR-2022-Update.pdf

Fontanari, Elena. 2018. Lives in Transit. An Ethnographic Study of Refugees’ Subjectivity across European Borders. London and New York: Routledge.

Guild, Elspeth and Didier Bigo. 2010. “The Transformation of European Border Controls”. In Extraterritorial Immigration Control. Leiden: Brill, 252-273.

Guild, Elspeth, Evelin Brouwer, Kees Groendendijk and Sergio Carrera. 2015. “What is Happening to the Schengen Border?” CEPS Paper in Liberty and Security in Europe 86

Guild, Elspeth. 2001. Moving the Borders of Europe. Nijmegen: Faculteit der Rechtsgeleerdheid.

Hameršak, Marijana and Iva Pleše. 2017. “Zimski prihvatno-tranzitni centar Republike Hrvatske. Etnografsko istraživanje u slavonskobrodskom kampu za izbjeglice”. In Kamp, koridor, granica. Studije izbjeglištva u suvremenom hrvatskom kontekstu. Emina Bužinkić and Marijana Hameršak, eds. Zagreb: Institut za etnologiju i folkloristiku, Centar za mirovne studije, Fakultet političkih znanosti – Centar za istraživanje etničnosti, državljanstva i migracija, 101-132.

Hameršak, Marijana and Iva Pleše. 2018. “Confined in Movement. The Croatian Section of the Balkan Corridor”. In Formation and Disintegration of the Balkan Refugee Corridor. Camps, Routes and Borders in Croatian Context. Emina Bužinkić and Marijana Hameršak, eds. Zagreb and München: Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research, Centre for Peace Studies, Faculty of Political Science University of Zagreb – Centre for Ethnicity, Citizenship and Migration, bordermonitoring.eu e.V., 9-41.

Hess, Sabine and Bernd Kasparek. 2017. “De- and Restabilising Schengen. The European Border Regime After the Summer of Migration”. Cuadernos Europeos de Deusto 56: 47-77.

İşleyen, Beste and Sibel Karadağ. 2023. “Engineered Migration at the Greek–Turkish Border. A Spectacle of Violence and Humanitarian Space”. Security and Dialogue

Juss, Satvinder S. 2013. “The Post-Colonial Refugee, Dublin II, and the End of Non-Refoulement”. International Journal on Minority and Group Rights 20: 307-335.

Kasparek, Bernd and Marc Speer. 2015. “Of Hope. Hungary and the Long Summer of Migration”. bordermonitoring.eu. Translation Elena Buck.

Kasparek, Bernd. 2016. “Complementing Schengen. The Dublin System and the European Border and Migration Regime”. In Migration Policy and Practice. Migration, Diasporas and Citizenship. Harald Bauder and Christian Matheis, ed. Palgrave Macmillan: New York, 59-78.

Kasparek, Bernd. 2016. “Complementing Schengen. The Dublin System and the European Border and Migration Regime”. In Migration Policy and Practice. Migration, Diasporas and Citizenship. Harald Bauder and Christian Matheis, eds. Palgrave Macmillan: New York, 59-78.

Kuster, Brigitta and Tsianos, Vasilis. 2016. “How to Liquefy a Body on the Move. Eurodac and the Making of the European Digital Border”. In EU Borders and Shifting Internal Security. Technology, Externalization and Accountability. Raphael Bossong and Helena Carrapico, eds. Cham: Springer, 45-63.

Long, Katy. 2013. “When Refugees Stopped being Migrants. Movement, Labour and Humanitarian Protection”. Migration Studies 1/1: 4–26.

Ombudswoman 2023. Izvješće pučke pravobraniteljice za 2022. Analiza stanja ljudskih prava i jednakosti u Hrvatskoj, https://www.ombudsman.hr/hr/download/izvjesce-pucke-pravoraniteljice-za-2022-godinu/?wpdmdl=15489&refresh=6465f2bc2565a1684402876

Picozza, Fiorenza. 2017a. “Dubliners. Unthinking Displacement, Illegality, and Refugeeness within Europe’s Geographies of Asylum”. In The Borders of "Europe". Autonomy of Migration, Tactics of Bordering. Nicholas De Genova, ed. Durham: Duke University Press, 233-254.

Picozza, Fiorenza. 2017b. “Dublin on the Move. Transit and Mobility across Europe’s Geographies of Asylum”. movements. Journal for Critical Migration and Border Regime Studies 3/1: 71-88.

Pozniak, Romana. 2023. “Temporalnost humanitarne skrbi. Politike upravljanja vremenom u režimu migracija”. Narodna umjetnost 60/2: 243-262.

Pravilnik o obrascima i zbirkama podataka u postupku odobrenja međunarodne i privremene zaštite, Narodne novine 85/16, https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2016_09_85_1863.html

Rozakou, Katerina. 2017. “Nonrecording the ’European Refugee Crisis’ in Greece. Navigating through Irregular Bureaucracy”. Focaal 77: 36-49.

Rydzewski, Robert. 2024. The Balkan Route. Hope, Migration and Europeanisation in Liminal Spaces. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

Stojić Mitrović, Marta. 2021. Evropski granični režim i eksternalizacija kontrole granica EU. Srbija na balkanskoj migracijskoj ruti. Belgrade: Etnografski institut SANU.

Vavoula, Niovi. 2015. “The Recast Eurodac Regulation: Are Asylum Seekers Treated as Suspected Criminals?”. In Seeking Asylum in the European Union. Selected Protection Issues Raised by the Second Phase of the Common European Asylum System. Céline Bauloz, Meltem Ineli-Ciger, Sarah Singer and Vladislava Stoyanova eds. Leiden: Brill, 247-275.

Zakon o privremenoj i međunarodnj zaštiti, Narodne novine 70/15, 127/17, 33/23, https://www.zakon.hr/z/798/Zakon-o-me%C4%91unarodnoj-i-privremenoj-za%C5%A1titi

Zakon o strancima, Narodne novine 133/20, 114/22, 151/22, https://mup.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/zakoni/ALIENS%20ACT%20(Official%20Gazette%20No%20133_2020).pdf

Zakon o strancima, Narodne novine 133/20, 114/22, 151/22, https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2020_12_133_2520.html

Zorn, Jelka. 2021. “The Case of Ahmad Shamieh’s Campaign against Dublin Deportation. Embodiment of Political Violence and Community Care”. Social Sciences 10/5: 154.

Walters, William. 2002. „Mapping Schengenland. Denaturalizing the Border“. Enviromental and Planning D: Society and Space 20/5: 561-580.