Pushback maps

In April 2024, when I set up my research device in front of the Lipa and Borići camps, my presence generated a word-of-mouth reaction, as someone identified as a writer specialised on border issues. People encamped there came to meet me to tell me about their game – according to the name given to the repeated attempts to cross the border, often followed by refoulement. From these numerous testimonies, a unanimous phrase emerged: “Police of Croatia: problem!”

The inhabitants of Bihać are at outposts to observe the repressive practices of the Croatian police. Taxi drivers, in particular, are regularly contacted after pushbacks, to take people from the place of refoulement or pushback (usually an isolated area in the forest or mountains), to the town of Bihać or the Lipa camp. As one of the drivers I met in Lipa explained:

We help them, it's for money, but we help them. They have enormous problems crossing the border. The Croatian police beat them up, take their money and phones and send them dogs. I've seen this violence first-hand.

Of the twenty-four exiles I met in Lipa, twenty-three had already tried to cross to Croatia. Most were on their fifth or sixth failed crossing; one had tried 26 times. During their refoulement, none of these people had received a copy of any document. This was the case for H*, R*, T* or U*, who did not even see a single written document during their refoulement. This is also the case for B*, who explains that he “signed a lot of papers, without understanding anything because they were in Croatian”.

The reason is simple: a large proportion of these deportations are carried out illegally. They even take place outside the frameworks built up over the last twenty years to organize expulsions, such as readmission agreements. The latter have proliferated under the impetus of European institutions in order to enable the rapid removal of a person to a state in which he or she has merely been staying or transiting.

The rationale behind the signature of readmission agreements is to enable accelerated state-to-state removals from an EU Member State to a non-EU Balkan State (of their own nationals or third-country nationals). In addition, the model promoted in the follow-up to EU applications encourages Balkan states to sign readmission agreements with third states from which many exiled persons originate. Pakistan and Bosnia-Herzegovina, for example, have concluded a readmission agreement in November 2020, effective since July 2021, as mentioned in a Commission's staff working document.

Readmission procedures are, however, subject to minimum procedural guarantees - in particular, receiving a written decision on the grounds for removal, being informed of one's rights and being able to understand the decision in a known language.

The recorded illegal removals go even further: they openly violate the European Convention on Human Rights (which prohibits collective expulsions on motives which are not individualized) and the 1951 Geneva Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, which alone should guarantee the principle of non-refoulement. According to this principle, states are prohibited from returning an individual to a country where his or her life or freedom is seriously threatened – i.e., if the individual is at risk of persecution, torture or degrading treatment on account of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion. Non-refoulement implies that all requests for asylum must be registered, and that the person making the request must be protected while his or her application is examined.

This text is included in the acquis communautaire and secondary legislation on asylum, with which both European institutions and Member States must comply. Nonetheless asylum requests expressed in Croatian border regions are not taken into account, as all testimonies concur in affirming. People seeking protection are well aware of this, and many have experienced it first-hand during their own refoulement: the aim of the game at this border is not simply to enter Croatian territory, but to reach the capital, Zagreb, where current practices are reputed to be more respectful of the right to asylum.

B*, a young Syrian who had just been turned back to Bihać despite his request for asylum to the Croatian police, put it simply: it is “a strange game, a completely crazy game!”. When we met, he was stunned by the idea that an institution could act so openly illegally on European soil.

A word has become widespread to describe the increasingly frequent refoulements carried out outside legal framework: pushback. Its variation, “to get pushedback”, has also become commonplace. The Balkan-based Border Violence Monitoring Network (BVMN) estimates that the term first appeared with the mass illegal returns from Croatia and Hungary to Serbia from 2016 onwards, when the official Balkan migration corridor closed (Bužinkić and Hameršak 2018; Dujmovic 2016). More generally, pushbacks are used in all chain removals from Austria to the southern Balkans – as documented notably by the Push Back Alarm Austria initiative from 2021. Illegal refoulements have also been widely observed at the internal borders of the Schengen area: in France, the Association nationale d'assistance aux frontières pour les étrangers (Anafé) publishes numerous reports on the subject, notably on the French-Spanish border. At the French-Italian border in particular, the recurrent practice of illegal pushbacks led to a ruling by the Court of Justice of the European Union on September 21, 2023. This ruling was echoed in a decision by the French Council of State on February 2, 2024, clarifying the procedures for carrying out removals to Italy, followed by a framework decision issued by the French Ombudsman on April 25, 2024, after a two-year investigation at the French-Italian border.

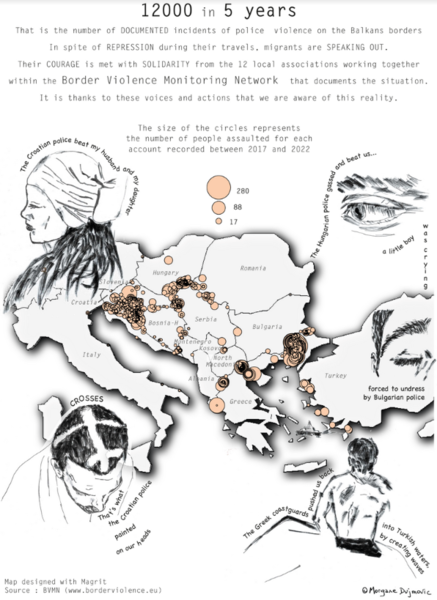

The corollary of pushbacks is the outpouring of violence made possible by the absence of rights. There have been countless reports by researchers (Robert 2021), associations (No Name Kitchen 2023; Amnesty International 2024) and institutions such as the United Nations documenting the violence perpetrated by police forces in the Balkan states, particularly since 2016 and the closure of the formal Balkan corridor. Now, the thousands of stories collected add up to a sum. Those compiled by the BVMN network can be consulted in an online database and an open-access Black Book of Pushbacks, a veritable painstaking effort to reconstruct the sequence of events and their massive nature. The first Black Book, published in 2020, listed 12,000 cases of violence, depicted on 1,500 pages; the second edition of the Black Book, published two years later, in 2022, counted 25,000 cases on 3,000 pages of description (more than double).

The map below spatializes these acts of violence and attempts to reveal, behind the numbers, the individuality of the people who gave their testimony – whose identities are anonymized by the drawing.

Data for Italy and Slovenia are not shown on this map, although it should be noted that violence is also recorded there. A case of violence counted is likely to concern the same person, if that person has been violated during different refoulements (multiple counts). This map was originally published in Migreurop's atlas (4th edition), published in 2022.

Detailed testimonies, compiled by BVMN according to a precise methodology, report various types of violence: insults; beatings; blows and injuries; theft, confiscation and destruction of property; dog attacks; armed threats; mutilation. Some practices are particularly inventive: intimidation and humiliation, such as marking people with a cross of red paint on the head, or forced undressing. They also deliberately endanger people by forcing them to swim out to sea or into icy rivers.

Testimonies go as far as allegations of rape and torture, which have been relayed by Amnesty International, among others, and taken up in court rulings. For example, in January 2021, the Court of Rome issued a judgment in favour of a claimant who had been subjected to illegal chain-removal between Italy, Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, based on the testimony he had given to BVMN and the report of Italian NGO ASGI which details the nature of the violence perpetrated by the Croatian police. In addition, BVMN carries out a monitoring of pushback litigation. This work by civil society volunteers, has become a necessity for documenting the facts, in the absence of any investigation by the public authorities.

10/11/2025

This text is taken from the series of portfolio articles “Rivers are deadly if you're not on the right side” previously published on Mediapart, Le Courrier des Balkans, visioncarto.net and Migreurop. This series of portfolio articles is the result of field research carried out in the spring of 2024 in several South-East European countries: Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro and Albania. This publication is sent to all interlocutors met in the field. To preserve their anonymity, the exiled people are referred to here by a randomly assigned letter, with their consent.

Author would like to thank the exiled people she met on these roads and along these rivers, the people from the collectives, associations, universities and institutions with whom she spoke, as well as Louis Fernier, Romain Kosellek, Eva Ottavy, Elsa Putelat and Marijana Hameršak for their invaluable contributions prior to and during this field mission.

Literature

Bacon, Lucie. 2022. “La fabrique du parcours migratoire sur la route des Balkans. Co-construction des récits et écritures (carto)graphiques”. PhD thesis, Université de Poitiers.

Bužinkić, Emina and Marijana Hameršak, eds. 2018. Formation and Disintegration of the Balkan Refugee Corridor. Camps, Routes and Borders in the Croatian Context. Zagreb: Zagreb and Munich: Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research, Centre for Peace Studies, Faculty of Political Science University of Zagreb – Centre for Ethnicity, Citizenship and Migration, bordermonitoring.eu e.V.

Dujmovic, Morgane. 2016. “Balkans, du corridor au cul-de-sac”. Plein droit 111/4: 23-26.

Dujmovic, Morgane. 2019. “Une géographie sociale critique du contrôle migratoire en Croatie : ancrages et mirages d'un dispositif” (A Social and Critical Geography of Migration Control in Croatia). PhD thesis, Aix-Marseille Univ.

Migreurop, Casella Colombeau Sara, ed. 2022. Atlas des migrations dans le monde. Libertés de circulation, frontières, inégalités. 4th edition. Paris: Armand Colin.

Robert, Harold. 2021. "Frontières. Le "game" des exilé·es, mythe de Sisyphe contemporain". Visionscarto.net.