Game

The term game has been used on the Balkan route for the past few years, in the period following the closure of the corridor that temporarily replaced the previously criminalized and dangerous individual border crossings, and its closure meant the recriminalization of irregularized crossings. This criminalization, in addition to increasing securitization as well as violence against refugees at the borders, is certainly closely related to the emergence of the game both as a practice and as a term, i.e. with the perception of crossing the border as a sort of repetitive game with barriers and difficulties that need to be overcome and levels that need to be passed in that game.

The term game is used equally by refugees, volunteers and workers of informal local and international humanitarian organizations, as well as smugglers. Today, this informal term, whose history of being taken from a non-migratory context, no matter how recent it may be, is not easy to determine exactly, and has found its way into the vocabulary of humanitarian organizations, local authorities in areas where refugee camps are located, and journalists dealing with irregularized migration in the Balkans.

Asif, a young man from Pakistan to whom we spoke in spring of 2022 in Bihać, described what the game means to him:

For others, it is very difficult, but for us – it’s like a game. When someone plays a game, he will either win or lose – some make it to Italy, but we always lose. If someone plays a game on their phone and always loses, they won’t delete the app, they’ll always try to win anyway, always try to win. It’s the same for us – we don’t want to go back to Pakistan – we want to win and one day we will.

Left side of frame – the Plješivica mountain, some of the people on the move travel across it to go on the game through Croatia. Right side of frame – a ruined house where some of our interlocutors lived while preparing for the game. Bihać, spring 2021. Photo: Bojan Mucko

Contemporary gamification of irregularized migrations, implied by the use of the word game for attempted and successful border crossings, is to some extent based on the sociological meaning of gamification, which on the one hand refers to the deliberate and conscious use of game elements in a non-game context, and on the other hand to the fact that “reality is becoming more gameful” and as such enables the acquisition of various skills, such as those related to problem solving or organization, developing motivation and commitment to a goal, as well as “creativity, playfulness, engagement, and overall positive growth and happiness” (Hamari 2019). Although in a completely different context, where it would be not only difficult but also extremely cynical to talk about overall positive growth and happiness, some gamification elements, i.e. the positive and intentional inclusion of game elements into everyday life in order to encourage participation and positive cognitive change or changes in behavior (Hamari 2019), are certainly important for understanding the game as an illegalized border crossing on the Balkan route. In this sense, the use of the word game could be seen as a seductive euphemism that encourages participation in a dangerous undertaking, but it is also a form of smuggling manipulation that presents the dangerous act of crossing borders as a game. In any case, while for some of the people on the move this is a word that denotes a (dangerous and difficult) attempt to cross the border, but is not related to additional game or gamer connotations, for others it also has these kinds of meanings, and could probably be interpreted as a form of consciously making the difficult and life-threatening migration seem easier, conceptually and in other manners (cf. Augustová 2021: 203).

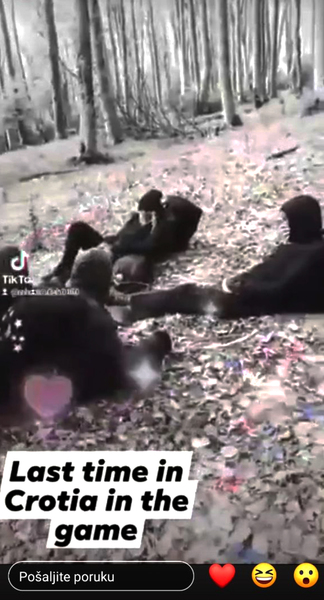

A group of people on the move go on the game. Bihać, December 2020. Still from a video note. Photo: Bojan Mucko

In game language, for many people on the move, entering Europe is possible only illegally, in this case through the Balkan countries, which requires strategy and tactics in outwitting a technologically far superior opponent, while the result is unpredictable until the very end. In addition, people on the move are also in a position of potential human prey, which is another association with games, with the role of predators being played by border police officers, and in some cases by self-organized anti-migrant groups such as the Styrian Guard in Slovenia, border patrols in Bulgaria or people’s patrols in Serbia. Although the asymmetry of power relations between the refugees and the various national police forces (which they encounter on their journey) mirrors the asymmetry of the distribution of power between the global North and South, from the perspective of the people forced to the game – it is naturalized as one of the many characteristics of this surreal game.

The naturalization is evident from our conversation with Zia, an Afghan with whom we spoke in early 2021 during his stay in the Bosnian-Herzegovinian migrant camp Lipa: “We will never give up. We will go on – that is our way. We will eventually succeed, and when we get to Italy – it will be better there. This is the gaming season. They [the police] do their job, but we have our way.” Conversations with many interlocutors in a similar position to Zia’s leave the impression that, from the perspective of people on the move, the outcome of the game does not depend as much on the (im)penetrability of the borders themselves or on the competence of the players, as it does on a logic of a higher order. Conversations about the future game and arrival at the desired destination are often concluded with “inshallah”, “God willing”.

Frozen tennis shoes – a scene from the game through Croatia. Bihać, spring 2021. Photo: Bojan Mucko

Claudio Minca and Jessica Collins conceptualize the game as a “spatial tactic” “based on a specific informal geography comprised of information travelling through social media, smuggling networks, makeshift and institutional refugee camps, and informal routes across the mountains, rivers and fields of the region” (2021). These two authors believe that the term game reflects a sense of pride that migrants feel equally if they successfully cross the border, as well as if they survive a pushback. “The practices related to The Game ultimately reveal the extraordinary determination of the refugees to create interstices, invisible networks and ‘holes in the walls’ that allow them, despite the difficulties, to challenge the border politics in the region.” In this outwitting competition between people on the move and the repressive apparatus, the game is also an expression of autonomous managing one’s own migratory movement (cf. autonomy of migration) and a disciplinary technique (Minca and Collins 2021) of irregularized movement expressed in the cruelty of the journey itself, but also in the violence that people on the move suffer due to pushbacks.

Waiting for favorable conditions to go to the game is an integral part of the mission, as it is understood in gaming culture as “a quest [...] that a [...] character, party, or group of characters may complete in order to gain a reward”. Waiting implies aligning parameters on many levels, from adapting to the season and waiting for the weather forecast, to coordinating with smugglers and members of the group with which the departure is planned. Fixed, general rules, however, do not exist – the scenario involves constant improvisation and adaptation to local circumstances, and the social, temporal and spatial context of an individual game. Given that the journey of people on the move often takes place through difficult, even dangerous terrain (cf. weaponized landscape), mountains and through forests, spring and summer are, according to interlocutors from Asif’s group, more favorable for departure due to the denser foliage that means less visibility. This time of year is certainly more favorable for crossings because of the terrain, which is easier to traverse with no snow or cold. Some groups of migrants self-organize when going on the game, while others try to cross borders with the help of smugglers, and some individuals decide to go on the game on their own. There are different types of games with regard to the method of movement, so names such as walk game, truck game, taxi game, train game, container game are common. Unlike the above expressions that belong to the English language, in conversations about the game, expressions that belong to the languages of the game participants are also used, and they also use them when they talk about the game in English. Thus, khod andaz is a game that a migrant goes on alone, it is a self-organizational game, and the literal translation from Urdu would mean “own style”. Guarantee game is a more expensive version of the game in which a smuggler (at least nominally) guarantees arrival at the desired location.

Improvised shelter in the woods – a scene from the game through Croatia. Bihać, spring 2021. Photo: Bojan Mucko

Preparations for the game involve obtaining basic camping equipment (such as backpacks, sleeping bags and portable phone chargers), shoes (sports sneakers for easier running through the woods), sports clothes and food necessary for staying in the extreme outdoors conditions for several days or even weeks. Equipment and food are obtained either through humanitarian donations with the help of local and international pro-migrant organizations, or purchased with their own funds. Both methods benefit the economy of the locale from which people go on the game. Local shop owners are also familiar with the concept of the game and the need for people on the move to be equipped for it, as evidenced by the name of the store GAME SHOP, opened in one of the containers inside the temporary camp Lipa. The list of food that is bought for the game (the list is variable and subject to improvisation) includes bread, water, candy and onions, as well as energy drinks, ketchup and mayonnaise, which, according to some of our interlocutors, they use because of the practicality of the plastic packaging, which lets them quickly squeeze the contents onto the bread while walking, everywhere, even in the forest. The field insight related to these two food items clarifies reports in the media from June 2020, when Amnesty International, based on insights of the Danish Refugee Council, after certain foreign and local media did the same, notified the public about one of the cases extreme violence by the Croatian police against refugees, which included smearing ketchup, mayonnaise and sugar on their hair. In its statement, the Ministry of the Interior rejects “the idea that a Croatian police officer would do such a thing, or have a motive for doing it” and wonders what the symbolism of smearing people with ketchup, mayonnaise and sugar would be. The key to the “riddle” is precisely that there is no symbolism involved – ketchup and mayonnaise are part of game food, and the modest means of survival found among refugees had been transformed into an ad-hoc means of humiliation by the sadistic act.

For the game, as well as for the entire journey, a key instrument – along with way signs, shelters, safe houses and knowledge about the route in general (cf. mobile commons) is the cellphone. The multifunctionality of this handy device enables navigation using GPS technology and offline use of maps to move and choose the safest routes, to avoid natural hazards, as well as for tactical outmaneuvering with the police.

In an interesting methodological process of participatory visual recording of the game, researcher Karolína Augustová asked her interlocutors to take photographs of the situations and details that best describe their experience related to the game. Among other things, they recorded the consequences of pushbacks in their photographs, and Augustová notes that fear and abuse, imprisonment and violence are the fundamental experiences captured in the photos (2021: 208). Our interlocutor Tamanna described her own experiences of pushbacks, one of which was particularly violent and traumatic, when the Slovenian police did not want to help her treat an injury sustained during the game, and a Croatian policeman deliberately additionally injured her foot. She and her husband successfully passed through Croatia on their thirtieth game. Pushbacks and the game, as this example shows, are the reality of everyday life for thousands of people on the move.

On social networks or in private messages, arrival at the desired destination is sometimes marked with game over. However, for all those who manage to pass the game, reaching their final destination also means the beginning of a new, equally demanding game, building a life in a new environment, or the beginning of a new cycle of returns and new attempts at crossings, i.e. new games.

A scene from the game from Croatia, shared on a social network. Spring 2021. Screenshot Photo: Bojan Mucko

29/12/2022

Literature

Augustová, Karolína. 2021. „Photovoice as a Research Tool of the 'Game' Along the 'Balkan Route'“. In Visual Methodology in Migration Studies. New Possibilities, Theoretical Implications, and Ethical Questions. Karolina Nikielska-Sekula and Amandine Desille, eds. Cham: Springer, 197-215.

Hamari, Juho. 2019. "Gamification". In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. George Ritzer and Chris Rojek, eds. Malden etc.: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Minca, Claudio and Jessica Collins. 2021. „The Game. Or, ‘the Making of Migration’ along the Balkan Route“. Political Geography 91.