Lipa Camp

As I approach the Lipa camp, one word springs to mind: lunar. In addition to the remoteness from the town, access is made difficult by a winding track almost 3 kilometres long, a series of potholes through the mountains leading to an uninhabited plateau. In front of the camp, the desert atmosphere contrasts with the architecture of fenced enclosures and the video-surveillance system overlooking it. The omnipresent signs forbidding entry and the taking of photographs are reinforced by the language repeated by all the members of the police security force, who warn that “the entire camp is video-protected”.

The desire to isolate exiles is palpable here; it is in line with the interests of the Bosnian and Croatian police, who thus keep men at a distance from the border, with a view to dissuading them from undertaking the game. For the municipal authorities, the removal from living areas is an assumed strategy, as the Lipa camp has periodically been used to evacuate exiles from abandoned buildings in the town, as the mayor of Bihać announced in the spring of 2021: “There are still places where migrants are staying (...) which we will also empty, clean and seal in the coming days”.

Furthermore, the camp's location is in line with the expectations of the EU, which has financed its infrastructure and operation through its program EU support to Migration and Border Management in BIH. Lipa is part of a series of camps set up in Bosnia-Herzegovina between 2018 and 2021, along with those in Bira, Sedra and Miral (since closed), and those in Borići, Ušivak and Blažuj, still in operation in spring 2024. The European grant that financed these Temporary Reception Centers (TRC, as they are officially known) totaled 100 million euros in expenditure over the years, asccoring to the IOM press release). The sum is regularly used as a sledgehammer argument to put pressure on the Bosnian authorities. As one can read from Migreurop report Endless Exiles, the EU's High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell, for example, in January 2021 seized on this financial argument to urge the Bihać and Una Sana authorities to get the Bira camp up and running again.

Temporary Reception Centre Lipa, April 2024. Photo: Morgane Dujmovic

In practice, however, these funds have been allocated to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), a UN agency and partner of the EU, which has been given the task of coordinating and managing the camps as part of the “Inter-Agency Migration Response” strategy. IOM has thus captured the bulk of funding from the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance for migration management and border control, establishing itself as a key partner in these areas (Ahmetašević et al. 2023). However, this configuration has changed since 2021: in line with the European Commission's objectives, which Bosnia-Herzegovina is reminded of in the Commission’s monitoring reports for its accession to EU (Ahmetašević et al. 2023: 48-57), the IOM is now moving towards what it calls a “plan for a transition to a state-owned migration response”– a formula that leaves little doubt about the previous interventionist strategy.

With the view to a handover to the Ministry of National Security, management of the Lipa camp has been transferred since November 2021 to the Service for Foreigners' Affairs (Služba za poslove sa strancima, better known in the field by its English acronym SFA). As one of the Service's officials put it in conversation in April 2024: "Lipa is the first center to be managed entirely by national institutions in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and represents a kind of pilot project in the transition plan expected by the EU and IOM". In 2021, the EU financed the construction of a dedicated detention area, transforming Lipa into a “Multi-purpose Reception and Identification Centre”, as formulated in the Commission’s monitoring report for the year 2022. This explains the tension that leads to restricting access to the camp, and the pressure not to provide information to outsiders – according to several words collected from exiles encamped there, in the spring of 2024.

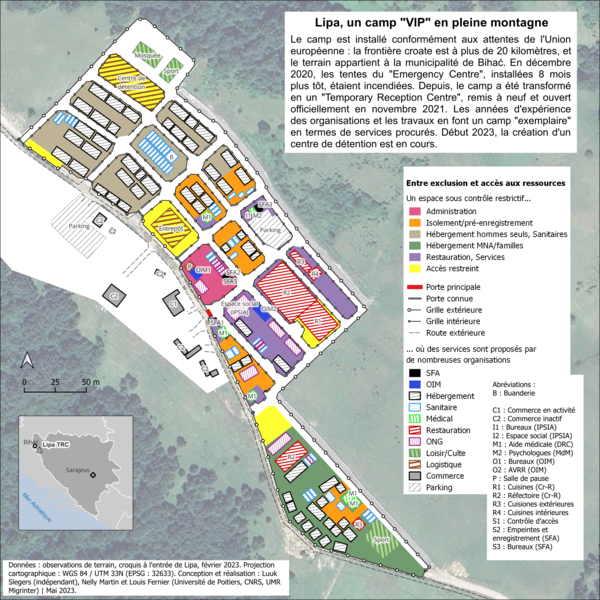

This is why geographer Louis Fernier has used a spatial reconstruction method in order to map the living space of the camp, based on evacuation plans and testimonies (Fernier and Dujmovic 2023).

Reconstitution of the Lipa camp plan, 2023, Louis Fernier, Nelly Martin and Luuk Slegers

In 2023, the people encamped at Lipa spoke of relatively good conditions, compared with camps in other countries (hence the term “VIP” camp on Louis Fernier's map). However, the remoteness of the camp, coupled with the inadequate resources of daily life, then contributed to what he analysed in his thesis as “spatial offenses” against exiles. Referring to the work of geographer Michel Lussault, “spatial offenses” encompass situations in which actors feel they no longer control distances, and are victims of intrusion or isolation.

In spring 2024, the words collected about poor living conditions are more numerous and vehement. Despite the rather clement accommodation conditions at this time (between 348 and 603 people registered at Lipa, for a capacity of 1,512 beds), exiles seem to lack everything in the camps that the EU and its delegation in Bosnia-Herzegovina pride themselves on funding. These words contrast with the “good-natured” atmosphere described in the IOM's fortnightly reports.

Inside the Lipa camp, the contrast is all the more striking given that the EU logo is everywhere, alongside those of the IOM and the dozen or so NGOs authorized to intervene in the camp to guarantee minimum reception conditions (cf. humanitarian Industry). As S* explains: “The doctor only comes for an hour on Mondays and an hour on Thursdays. If someone is about to die, what are they going to do?” Such descriptions echo the opinions of many local observers: indeed, these precarious housing conditions motivate the regular presence in the field of collectives such as No Name Kitchen, whose volunteers try to make up for the shortage of foodstuffs or so-called Non Food Items (clothing, hygiene kits, etc.) (cf. distro).

The access road to the camp is another evocative symbol of this contrast. On this dusty, cracked, unmaintained road, visitors come across all-terrain vehicles and vans emblazoned with the EU logo. The latter are the result of expensive donations: in particular, black all-terrain vehicles worth 370,000 euros were donated in March 2023 to the Directorate for the Coordination of Police Forces (which took over responsibility for camp security the previous year), representing a donation of 725,000 Bosnian Convertible Marks from the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA) project. Moreover, in the mark of the project: “Special Measures to Support the Response to the Refugee and Migrant Situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina Phase III“, white pickups and vans were donated in February 2024 to the Border Police to “support operational actions in regional offices”, like the one in Bihać, worth 500,000 euros.

On the other hand, segregation and destitution represent good opportunities for some local shopkeepers. Several stores are tolerated on the wasteland adjoining the camp: necessary for the encamped people, the products sold there are also appreciated by the police officers who come there daily to buy bread, cigarettes... Several derelict sheds suggest an important past activity; among these is the trace of a store with a cynical name: The Game Shop.

Game shop Lipa, April 2024. Photo: Morgane Dujmovic

Lipa markets, April 2024. Photo: Morgane Dujmovic

In the main private shop still in operation, one can find everything for the game: warm clothing and walking boots for men; sleeping bags; and SIM cards that can only be used for internet in Croatia, Slovenia and Italy. One of the salesmen describes the profits made locally from migrants in the following words in April 2024:

People here are generally not happy about the migrants’ presence, they accuse them of the slightest theft or criminal act. But at the same time, the locals make a big business out of it. Just imagine, if you think of the sales, the accommodation, the taxis!

18/9/2025

This text is taken from the series of portfolio articles “Rivers are deadly if you're not on the right side” previously published on Mediapart, Le Courrier des Balkans, visioncarto.net and Migreurop. This series of portfolio articles is the result of field research carried out in the spring of 2024 in several South-East European countries: Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro and Albania. This publication is sent to all interlocutors met in the field. To preserve their anonymity, the exiled people are referred to here by a randomly assigned letter, with their consent.

Author would like to thank the exiled people she met on these roads and along these rivers, the people from the collectives, associations, universities and institutions with whom she spoke, as well as Louis Fernier, Romain Kosellek, Eva Ottavy, Elsa Putelat and Marijana Hameršak for their invaluable contributions prior to and during this field mission.

Literature

Ahmetašević, Nidžara, Manja Petrovska, Sophie-Anne Bisiaux and Lorenz Naegeli. 2023. Repackaging Imperialism: The EU – IOM Border Regime in the Balkans. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute.

Fernier, Louis and Morgane Dujmovic. 2023. "Frontières violentes, recherches à risque : s’engager par le mouvement". Valenciennes: CNFG Conference Paper.