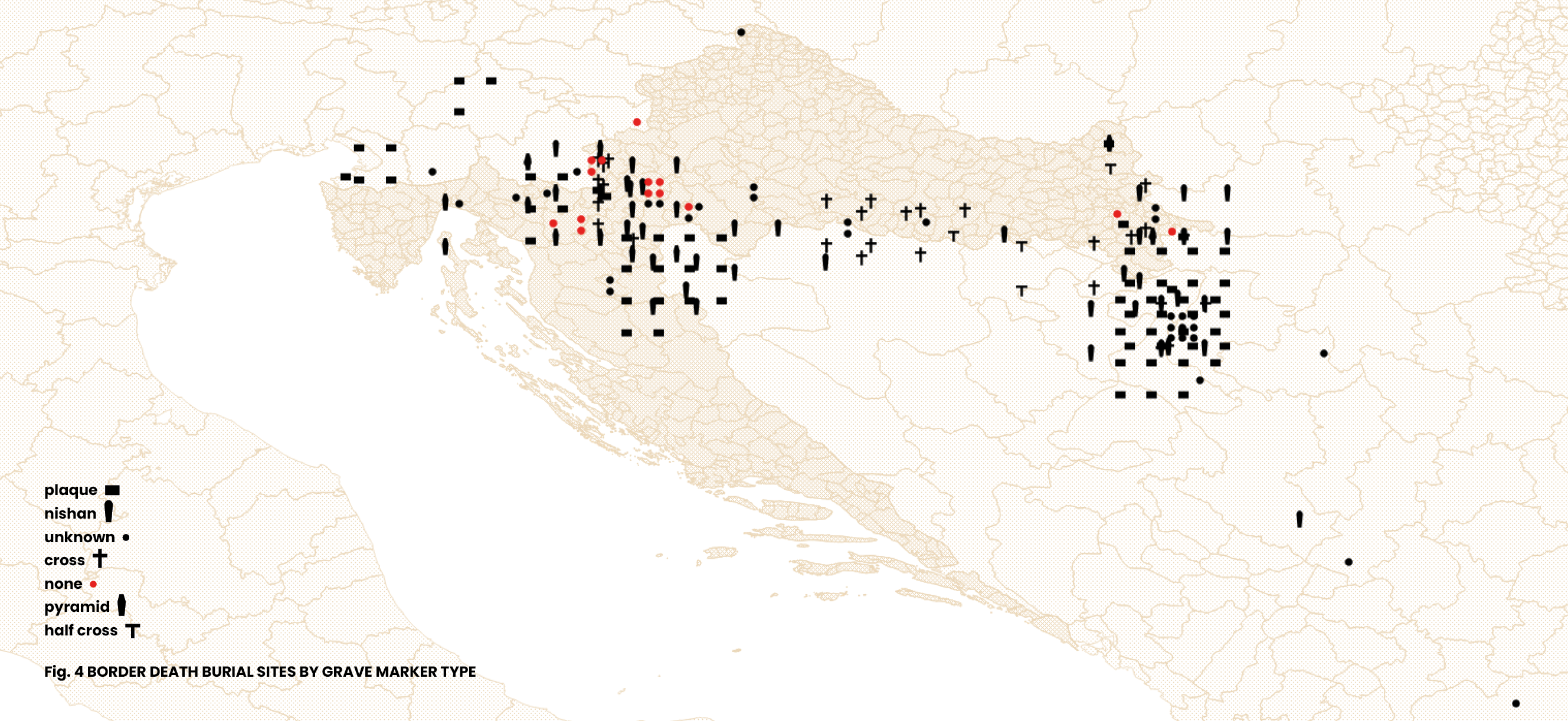

Map of Grave Markers

The forms of grave markers reflect local practices and the ways in which border deaths are integrated into them. Our categorization of grave markers is not based on some standardized sepulchral terminology or classification, but on local names and reasoning used to distinguish among various types—or rather functions—of grave markers. The same grave marker shape can have a different name depending on the immediate sepulchral context. In multiconfessional cemeteries a distinction is made between the “pyramid” (piramida), a religiously neutral grave marker with an elongated form and a pyramidal top, and the “nishan” (nišan, bašluk), a religious grave marker with the same elongated shape, but which also displays engraved or painted Islamic symbols such as a half moon and star. In the religiously homogeneous, Muslim, or Orthodox cemeteries, the same form, with or without its distinctive Islamic symbols, indicates a “nishan,” i.e., a standard, traditional Muslim grave marker.

A substantial number of graves are left unmarked. Unmarked graves are burial sites without a marker or at least without an element that can be recognized as a symbolic marker. Broken pieces of marble used for the graves of three unidentified drowning victims in the Kupa/Kolpa River are recognized as physical grave markers, but not as symbolic markers, and are therefore categorized as “none,” meaning unmarked, on this map.

In urban multi-confessional cemeteries, the grave markers of those who died at the borders are often distinctively in the shape of pyramids, plaques, or nishans, whereas the grave markers in smaller, rural cemeteries tend to match those of the majority of other graves: crosses or nishans. The distribution of markers on the map is therefore telling of the religious traditions in local cemeteries, with most crosses in Christian dominated areas such as Posavina. However, it is important to acknowledge that these patterns are temporal and multilayered, since the grave markers not only deteriorate and disappear over time, but also, in some instances, transform from non-religious to religious and vice versa.

This map is part of a series of visualizations of data on migrant graves in Croatia and surrounding countries. For other maps, see: Map of Grave Locations, Map of Causes of Death, Map of Grave Inscriptions and Map of Grave Markers Materials.

***

Border death burial sites marked on this map have been identified based on media reports, personal accounts, data requests todifferent institutions, and field visits to cemeteries. For complementary data about border deaths, see the ERIM Map of Border Deaths and 4D database. Information sources for each burial site shown on the map are provided alongside each location in a dataset available here. The dataset includes several graves outside Croatia that fall beyond the geographic scope of this set of visualizations.The locations of individual graves were recorded using a mobile phone GPS, which may result in slight coordinate variations even for exact positions. These GPS coordinates were then integrated into a GIS (Geographic Information System) tool to produce the maps. For the spatial visualizations, QGIS (open-source mapping software) and professional design software were used to create the maps. Geographic data was obtained from multiple sources including OpenStreetMap, The Humanitarian Data Exchange, and DIVA-GIS.

Documenting border deaths and burial sites was one of the research strands of the international research project ERIM, The European Regime of Irregularized Migration at the Periphery of the EU: From Ethnography to Keywords, coordinated by the Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research in Zagreb from 2020 to 2024. Following the project's completion, the work has been continued by several former project associates and others.

8/12/2025