Map of R*’s Journey from Tunisia

I sought to give an account of the gradual border violence other than in the words of the researcher, which tend to neutralize violence to objectify it. The methodology I employ in the field aims to facilitate the expression of narratives and knowledge derived from the experience of borders.

My approach is to include people in the representation of their journey, through participatory mapping workshops. Beyond traditional social science methods of observation and interviewing, this proposal allows drafting an emotional and experiential cartography of European borders.

When imposed by the violence of the border context (lack of intimate space, evictions, shelter deprivation), these workshops take place in a converted vehicle (the CartoMobile), designed as a space for respite, creation and work, better suited to self-expression and intellectual reflection. With this mobile research laboratory, my aim is to include exiled people in the representation of their own narrative, where migration policies encourage them to be sidelined, invisibilized and silenced.

Since 2022, this approach has given rise to a traveling exhibition and the emergence of an art-science collective bringing together cartographers and some sixty exiled people in the Balkans, on the French borders and in the central Mediterranean.

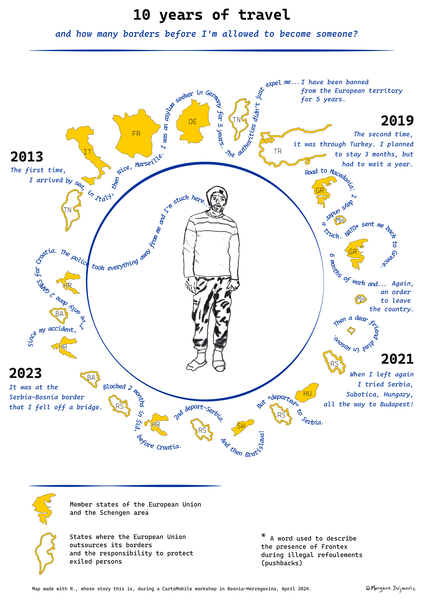

In the spring of 2024, I took the CartoMobile to the outskirts of the Lipa and Borići camps. It welcomed several people, all affected by gradual institutional violence during their journey to Europe. The cartographic work I undertook with R* illustrates his journey from Tunisia to Bosnia-Herzegovina, attempting to adopt his gaze, to approach the sensitive dimension of his experience. The resulting narrative map bears the title of a quotation from R*: “Ten years of travel, and how many borders before I have the right to become someone?” In R*’s map below, all quotations have been translated from French by the author.

R*'s individual journey reflects macro realities. Like J* and X*, this is not his first time in Europe: in 2013, he left Tunisia following the Arab Spring, to reach Italy by sea, then France and Germany. Five years passed before his asylum application was rejected and he was deported back to Tunisia with a five-year ban.

R* set off again in 2019, this time via Turkey. This was the beginning of a series of deportations across seven countries in south-eastern Europe. Over the course of this five-year journey, until our meeting in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the map shows how the border gradually thickens and the journey fragments, seeking new routes through EU member states (Greece, Hungary, Slovakia and Croatia), or non-member states that apply the border control measures promoted by the former (Northern Macedonia, Kosovo, Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina). This stage of the journey reveals the “cascading” border that can be experienced when approaching the EU, when one is engaged on roads made illegal.

R*'s testimony is also among those that question the role of Frontex, the agency being mentioned as responsible for illegal and violent refoulements at two stages of the journey (at the Macedo-Greek and Croatian-Bosnian borders).

From R*'s perspective, the border experience can be understood on several levels. In addition to geopolitical and administrative barriers, there are physical, geographical and individual borders: on the one hand, the Mediterranean Sea, the Balkan mountains, forests and border rivers, such as the one he accidentally fell into in 2023; on the other, his own body, whose capacities have deteriorated since that accident and his hospitalization of several months. This is partly how R* explained his difficulties in undertaking the game to Croatia (two attempts in one year).

The fact that he considers himself “stuck” in Bosnia-Herzegovina is also the effect of the tightened control arrangements at the Bosnian-Croatian border, in view of the whole journey:

I left 10 years ago, I've crossed more than 10 countries. I've been stuck here in Bosnia for 10 months. Finally, I was stopped here at the Croatian border. Of all the borders, Croatia is the most difficult.

However, the words that accompanied the mapping process reflect his lucidity about the dissuasive function of indiscriminate police violence: “They hit a lot to scare us, to prevent us from crossing the border again. But they're afraid of terrorists, not people like us”.

With R*, our graphic choices sought to convey this retrospective experience. That of a body affected by the hardships of travel, at the centre of the map. That of a border that imprisons, hence the circular arrangement of the countries crossed. That of a journey fragmented by multiple expulsions, rendered by the dislocation of spatial landmarks. That of a sticky, omnipresent and insidious illegality, in the image of the snatches of experience that wind their way through. That of long, cyclical time, of the game's eternal recommencement. And finally, that of an uncertain and misunderstood condition, as reflected in his question: “How many borders [do I have to cross] before I have the right to become someone?”

On the scale of journeys lasting several years, border violence permeates memories as much as future prospects. B* deplores the fact that his little brother's legs bear the scars of the long journey from Syria through the Balkans. H* describes how his health has plummeted since his confinement in Serbia, showing me the anti-anxiety medication given to him in the Lipa camp: “I used to be fit, very sporty, and now: cigarettes, psychologist, medication”. As for E*, he talks at length about his condition as a black man in the Balkans, since his arrival on an island on the Greek-Turkish border.

The physical and psychological impacts of Balkan journeys continue to be observed across time and distance, for example in those who later reach the French-Italian border, as testified by the work of Médecins du monde in Briançon.

In the map below, made at the Terrasses Solidaires Refuge in Briançon in 2023, Marouane has recomposed his Balkan route experience by associating an emotion or key word with each country he crossed: agony [agonie, in French], for Morocco, racism [racisme] in Turkey, fear [peur] in Serbia and death [mort], in Hungary. More generally, when exiled people escape from the Balkans, their retrospective account takes shape of of a veritable “journey of death” (Courtois 2023).

Map of Marouane's Balkan route, made retrospectively in Briançon, 2023, Marouane and Morgane Dujmovic

While these stories of border violence are singular, they are recurrent enough to be significant and instructive. The huge amount of the testimonies reveals the experience of a “mobile” border, a “borderity” that is exercised along the way, with little discernment (Amilhat Szary and Giraut 2015). Several authors have shown that violence is an integral and structural part of the border, either as a means of asserting the State (Jone 2016), or as a means of depriving people of certain resources (Mezzadra and Neilson 2013).

From the accounts of R* and the other people I met at the Bosnian-Croatian border, I understand that this deprivation targets personal achievements and fairly simple life projects, in the face of which the warlike geostrategy deployed by the EU seems disproportionate.

Finally, testimonies from the Balkans lead to the chilling realization that physical and psychological violence have become part of the border control strategies of several European states, supported in this by the EU. The border filter no longer operates so much on the level of rights linked to status (since these rights are massively violated), but on each individual's ability to survive this institutionalized violence.

Those who emerge unscathed are the survivors of the violence of the European border.

10/11/2025

This text is taken from the series of portfolio articles “Rivers are deadly if you're not on the right side” previously published on Mediapart, Le Courrier des Balkans, visioncarto.net and Migreurop. This series of portfolio articles is the result of field research carried out in the spring of 2024 in several South-East European countries: Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro and Albania. This publication is sent to all interlocutors met in the field. To preserve their anonymity, the exiled people are referred to here by a randomly assigned letter, with their consent.

Author would like to thank the exiled people she met on these roads and along these rivers, the people from the collectives, associations, universities and institutions with whom she spoke, as well as Louis Fernier, Romain Kosellek, Eva Ottavy, Elsa Putelat and Marijana Hameršak for their invaluable contributions prior to and during this field mission.

Literature

Amilhat Szary, Anne-Laure and Frédéric Giraut. 2015. Borderities and the Politics of Contemporary Mobile Borders. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Courtois, Maïa. 2023. "Après “le voyage de la mort”, les Terrasses de Briançon offrent un répit aux exilés". Infomigrants.net.

Jones Reece. 2016. Violent Borders. Refugees and the Right to Move. London and New York: Verso.

Mezzadra, Sandro and Neilson Brett. 2013. Border as Method, or the Multiplication of Labor. Durham: Duke University Press.

Documents

Karta R*-ova putovanja

Download 437 KB