Seven Days Paper

"Seven days paper" is the colloquial term for documents regulating transit through Croatia in 2022 and 2023. During this period, which does not yet have a specific name but could be called the shadow corridor period in analogy with the Balkan corridor, more than a hundred thousand refugees and other migrants passed through Croatia using various documents. The oldest of these documents, the return decision, was in effect for seven days, and thus activists, humanitarian workers, refugees, and other migrants often generically referred to them collectively as "seven days paper". The return decision is designed and legally defined as part of the deportation infrastructure: its first, nominally voluntary stage. In other words, it is an administrative framework for self-deportation, as Hamza, who was detained in Ježevo in the spring of 2016, described his formally voluntary return to Iraq.

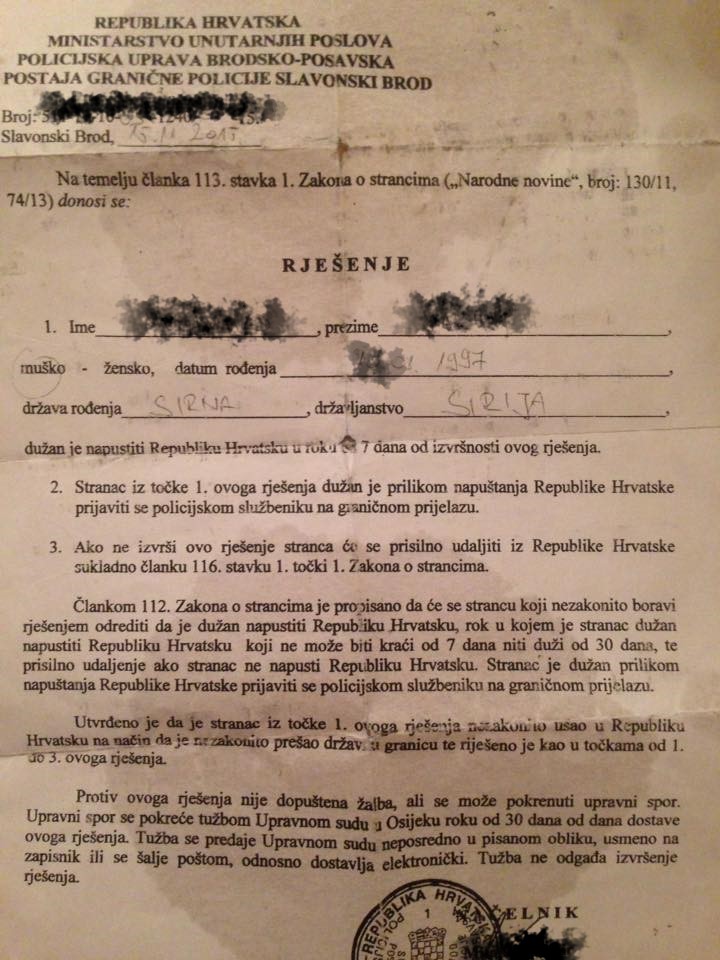

Historically, the seven days paper is akin to the Greek harti, another type of return decision, but with a longer duration (six months or a month), from the long summer of migration (e.g., Rozakou 2017: 37-38; Rydzewski 2024) and variations of this document in the countries along the Balkan route. In the summer of 2015, North Macedonia introduced amendments to its asylum act that “allowed the use of public transport for persons who had illegally entered the country by issuing a 72-hour certificate, modeled after the document that certified that a person expressed intention to seek asylum in Serbia” (Stojić Mitrović 2021: 102). The shared migration regulation strategy with the “72-hours paper – first introduced by Serbia and later adopted by Macedonia – substantially contributed to the establishment of the formalized corridor in the south of the Balkan route in early autumn 2015” (Beznec et al. 2016: 61). In Croatia, movement within the corridor was also regulated by a return decision, at least until the end of 2015, specifically a decision on voluntary departure from the Republic of Croatia within seven days (Aliens Act, Narodne novine 11/13, Article 113) while refugees were defined as a third-country national in the return procedure. Due to the speed of transit at that time, which left little room for the creation of mobile commons, knowledge about the journey itself, and due to the circumstance that the so-called registration of refugees in the corridor in Croatia was conducted in parts of the Slavonski Brod camp to which most employees and volunteers were denied access (Hameršak and Pleše 2017: 108-111), the document or documents issued in Croatia for transit purposes at that time were not the subject of conversations and discussions, nor did they receive a colloquial name comparable to those mentioned here.

The expansion of the functions and competencies of the return decision in the Croatian context has not always been aimed at tolerating or facilitating transit. After the corridor was closed in 2016, the return decision became an important administrative part of the implementation and concealment of the scale of pushbacks. At the time, Croatian police, for instance, at police stations formally issued return decisions to people intercepted in transit, but it did not hand them out. Subsequently, they were pushed back across the green border into Serbia. As detailed in a letter from the Ombudswoman to the State Attorney’s Office in 2018, after being escorted to a police station near the border:

Foreigners who have been issued return decisions and given a deadline to leave Croatia were, in subsequent police actions, deprived of their liberty without legal basis. They are then transported in police vehicles (police vans, and even buses!) to the jurisdiction of another police administration, which does not have the necessary documentation regarding their reception and cannot provide information. This represents a violation of international and national regulations governing deprivation of liberty, and certainly calls into question the motivations behind such actions (emphasis by M. H.).

After years of such practices, which led to the invisibilization of migrant movements and the expansion of violence at the borders, return decisions began to be used in the spring of 2022 as documents for the temporary decriminalization of migrant movements towards the West. As Romana Pozniak (2023: 254) formulated, return decisions temporarily, albeit very arbitrarily, “regularized” the status of people on the move. This change undoubtedly came from above, simultaneously with changes in neighboring countries (Hungary, Slovenia, Austria, and Italy also tolerated or facilitated transit during this period) or in some form of a domino effect incomprehensible to outsiders. The return decision went from being an instrument for backward movement and deportation to once again serving as an instrument for forward movement and transit.

The return decision in issue is based on the Croatian Aliens Act (Narodne novine 133/20, 114/22, 151/22), which stipulates that a person “who is staying illegally in the Republic of Croatia” “shall leave the [European Economic Area]” within the designated time limit. According to the act, this period cannot be less than seven days and no longer than thirty days. In this context, it was regularly seven days, as referenced in the document’s informal name.

After the meeting of interior ministers in March 2023, and concurrently with the implementation of the reform of the Schengen Information System (SIS), which made return decisions issued in one Member State visible to all Member States, the Croatian police began to issue return decisions much less frequently. Instead, they started to massively conduct registrations and issue documents called registration certificates. This document is based on the Act on International and Temporary Protection (Narodne novine 70/15, 127/17, 33/23). According to the accompanying ordinance (Narodne novine 85/16, Article 3), it “proves that a third-country national or stateless person is registered in the Information System of the Ministry of the Interior [...] as an asylum seeker in the Republic of Croatia.”

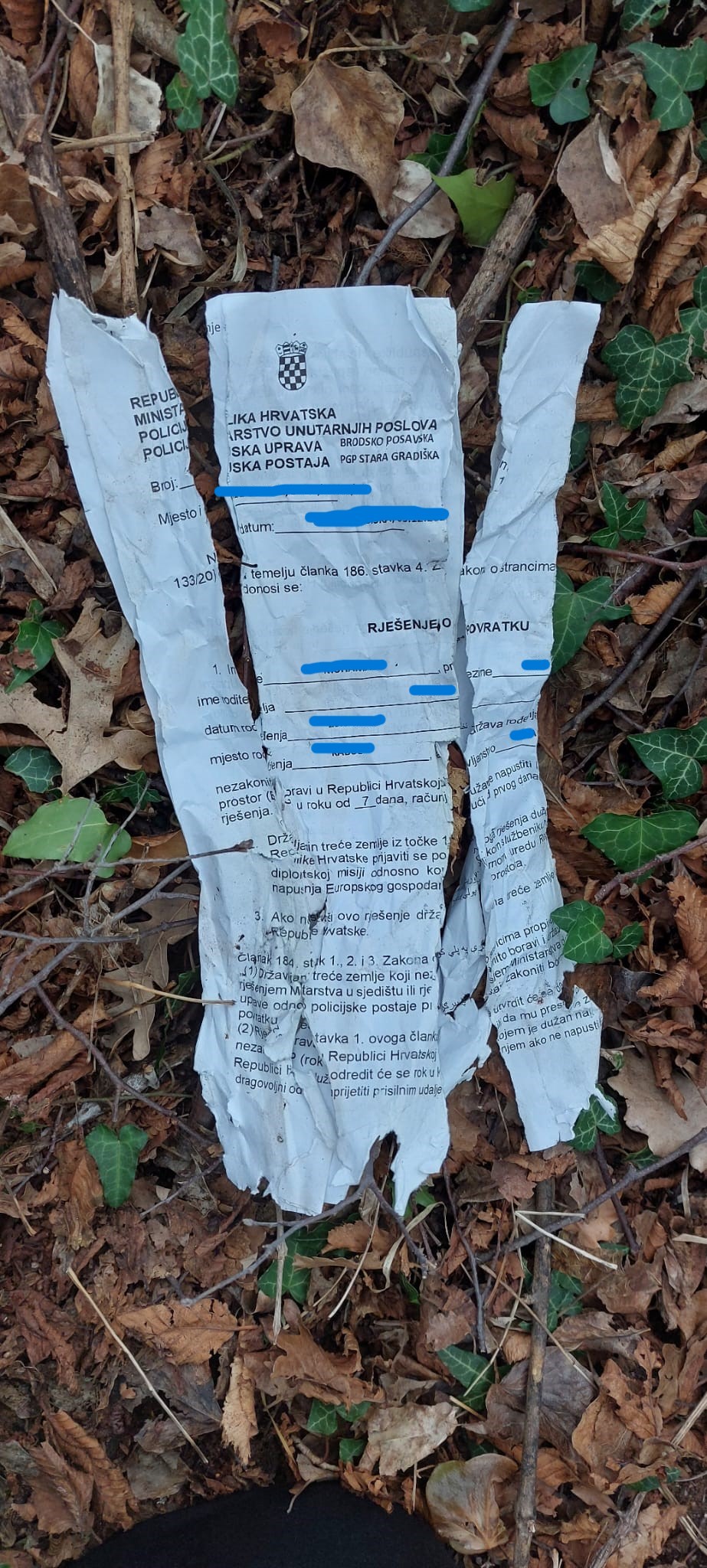

In addition to requiring registration in the information system, or, in other words, fingerprinting (which was not necessarily part of the return decision procedure), the registration certificate differed from the return decision in terms of “duration.” It regulated transit only until the end of the following day from the date it was issued. By then, the registered person was supposed to, as stated in the certificates we saw, “report to the Reception Center for Asylum Seekers, Sarajevska 41, Zagreb,” i.e., Porin. Months after the registration certificate became the dominant form of regulating transit through Croatia, some people on the move and activists continued to refer to the transit document as seven days paper. Additionally, terms like stay paper, permit of stay in Croatia, registration paper, or simply paper were still in use. In reports on pushbacks, the term quitte was mentioned, but we did not encounter it in our personal exchanges. During controls and routine profiling on trains and buses, which were frequent but primarily performative during this period, police officers would ask passengers for documents or papers. From brief conversations with people in transit and their behavior during these controls—automatically pulling out folded, freshly printed white papers from bags and pockets without unfolding them, as if the content was secondary—it was clear that many of them were not aware of the content of the document they had, especially if the police had given them a registration certificate, as it was issued only in Croatian, unlike the return decision, which had to be multilingual. This means many did not know the potential long-term consequences of transit with such documents: deportation under the Dublin Regulation upon arrival in another EU country, activation of the Schengen Information System, etc. Numerous discarded, often torn-up return decisions or registration certificates seen along the green borders at crossing points into Slovenia (e.g., Harmica/Rigonce or Buzet/Rakitovac) and Italy (Socerb/Dolina) were paper trails of attempts to avoid immediate threats: readmission to Croatia, detention in the country of arrival, etc. Some people on the move avoided transit with the seven days paper for the same reason, and in 2023, fake seven days papers appeared, used to “invisibly” transit through Croatia.

During this period, everyone involved—migrants and refugees, government representatives and police, as well as others such as transport providers, landlords, and hotels—used and perceived the return decisions and registration certificates as documents that temporarily decriminalized the movement of the undesirable. Transit through Croatia no longer primarily involved clandestine movement and hiding. Instead, it took place on public transportation, such as trains, buses, and taxis, relying on existing public transit infrastructure (train station waiting rooms, toilets, etc.), nearby public facilities and areas (parks, public fountains, etc.), abandoned buildings (Banka and Diskont in Zagreb), as well as accommodation in hotels and hostels, private rooms. In addition, humanitarian infrastructure was established in response to this movement in Rijeka and briefly in Zagreb (cf. Paromlin). In the same period, pushbacks became less frequent and were concentrated at the border (Ombudswoman 2023: 200 and ECRE 2022: 25-29), especially in the areas of Banija and Kordun. The journey from Bosnia and Herzegovina or Serbia to Italy again began to be measured in days, rather than years. However, in the late autumn of 2023, in response to reactions from central EU states, the reactivation of controls at internal Schengen borders, and other events that are difficult to single out at this moment, transit was once again predominantly criminalized and halted. News of deaths in rivers within the Schengen area and brutal pushbacks at external borders became increasingly common again.

Unlike various laissez-passer documents, transit visas, and other types of passes, including the so-called Nansen passport (cf., e.g., Long 2013), which allowed hundreds of refugees between the two World Wars to travel to places where they, by their own assessment, had better conditions for continuing their lives, the seven days paper was recognized as a transit document only in the second step, through practice. This is not an anomaly of the system, but an integral dimension of its functioning, as can be clearly seen from a comparative perspective. For instance, the Greek asylum seeker status certificate (the so-called roz karta) was in widespread use as a stay permit or residence permit, as discussed by Heath Cabot (2012), or consider the practices of non-registration of migrants in Greece during the long summer of migration, as described by Katerina Rozakou (2017). Rozakou emphasizes that ethnographic research on bureaucratic procedures at borders shows that these techniques of governance and population regulation are embedded in the social and cultural environment, constantly changing, questionable, and chaotic. In this context, documents in which illegality and legality interweave acquire unexpected meanings, while the fantasy of bureaucratic control remains intact (Rozakou 2017: 39-46). From this perspective, the seven days paper is recognized as a materialization and one of the tools of the “tacit agreement” (Kasparek 2016) between migratory movements and states at the external border of Schengen and the EU. Moreover, as Rozakou concludes (2017: 46), false or pseudo-bureaucratic procedures prove to be a crucial element in maintaining the state and the state apparatus, at least when it comes to the European migration regime, and they are as accepted by all involved, despite the fact that they are recognized as departing from the bureaucratic framework and nominal order.

15/12/2023

Literature

Beznec, Barbara; Marc Speer and Marta Stojić Mitrović. 2016. Governing the Balkan Route. Macedonia, Serbia and the European Border Regime. Belgrade: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Southeast Europe.

Cabot, Heath. 2012. “The Governance of Things. Documenting Limbo in the Greek Asylum Procedure”. Political and Legal Anthropology Review 35/1: 11-29.

ECRE. 2022. Country Report. Croatia.

Hameršak, Marijana and Iva Pleše. 2017. “Zimski prihvatno-tranzitni centar Republike Hrvatske. Etnografsko istraživanje u slavonskobrodskom kampu za izbjeglice”. In Kamp, koridor, granica. Studije izbjeglištva u suvremenom hrvatskom kontekstu. Emina Bužinkić and Marijana Hameršak, eds. Zagreb: Institut za etnologiju i folkloristiku, Centar za mirovne studije, Fakultet političkih znanosti – Centar za istraživanje etničnosti, državljanstva i migracija, 101-132.

Kasparek, Bernd. 2016. “Complementing Schengen. The Dublin System and the European Border and Migration Regime”. In Migration Policy and Practice. Migration, Diasporas and Citizenship. Harald Bauder and Christian Matheis, eds. Palgrave Macmillan: New York, 59-78.

Long, Katy. 2013. “When Refugees Stopped being Migrants. Movement, Labour and Humanitarian Protection”. Migration Studies 1/1: 4–26.

Pozniak, Romana. 2023. “Temporalnost humanitarne skrbi. Politike upravljanja vremenom u režimu migracija”. Narodna umjetnost 60/2: 243-262.

Ombudswoman 2023. Izvješće pučke pravobraniteljice za 2022. Analiza stanja ljudskih prava i jednakosti u Hrvatskoj

Rozakou, Katerina. 2017. “Nonrecording the ’European Refugee Crisis’ in Greece. Navigating through Irregular Bureaucracy”. Focaal 77: 36-49.

Rydzewski, Robert. 2024. The Balkan Route. Hope, Migration and Europeanisation in Liminal Spaces. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

Stojić Mitrović, Marta. 2021. Evropski granični režim i eksternalizacija kontrole granica EU. Srbija na balkanskoj migracijskoj ruti. Belgrade: Etnografski institut SANU.