Dublin

For many, the first association when hearing “Dublin” is the city in Ireland, which is not necessarily the case for asylum seekers, humanitarian workers, human rights activists, and others engaged in the asylum system. They use the term “Dublin” for deportations, euphemistically termed Dublin transfers, from one European Union Member State to another. The term stems from the Dublin Convention, an agreement among EU states about the distribution of asylum juridisctictions signed in Dublin in 1990. This convention, which came into force in 1997, was replaced by the Dublin Regulation adopted in 2003, known as Dublin II, which itself was replaced in 2013 by the new Dublin Regulation or Dublin III,which will certainly not be the last one. According to the Dublin Regulation, the responsibility for processing asylum claims lies with the Member State in which the asylum seeker first entered. This means that countries that are located on the EU's external borders bear exclusive responsibility for those who enter the European Union by land and sea routes. If a person seeks asylum in a country that is not the first country of entry (e.g., Germany or Austria), according to the Dublin Regulation, he or she may be forcibly and involuntarily returned to the country of first entry or presumed first entry (e.g., Croatia), with the possibility of being returned to a country where the person has never been, examples of which we discovered during field research.

The Dublin Regulation is one of the five legislative pillars of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). Together with Eurodac, the EU fingerprint database of asylum seekers or, as it is also known, the EU digital border (Kuster and Tsianos 2016), it is one of the CEAS cornerstones (Kasparek 2016: 62). Since the Eurodac Regulation came into force in 2015, national police forces and Europol have been authorized to use the Eurodac biometric fingerprint database to prevent, detect, or investigate terrorist acts or other criminal activities (Vavoula 2015: 252), thereby labelling asylum seekers as potential criminals or terrorists. This assumption aligns with other assumptions about asylum seekers as individuals who falsely represent themselves or who seek to exploit the international protection system in some way. Nominally, Dublin prevents abuses of the asylum system, but in reality, it prevents asylum seekers from choosing their place of refuge based on familial and friendly ties, information about opportunities for regularizing their status, working conditions, access to healthcare, and more. The choice of destination country within the Dublin framework is redefined as exploitation or abuse of the asylum system, pejoratively termed “asylum shopping.” Envisaged as a mechanism to prevent so-called secondary movements, Dublin fosters hypermobility among potential or former asylum seekers and refugees “trapped in transit” (Picozza 2017a: 239), or “lives in transit” (Fontanari 2018). Among numerous examples, we highlight Dublin deportations from Switzerland to Croatia in 2023, where, as articulated by the Swiss activists we contacted, “by the end of August, 157 people were transferred to Croatia, many of them families. All families we know of left Croatia shortly afterwards, either returning to Switzerland or moving to another country.”

The focus of Dublin on peripheral countries comes from its background as an extension of the Schengen system of open internal borders and strictly controlled external borders of Europe. This historical link between Dublin and Schengen is recognized today in the inclusion of four non-EU countries—Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland—in both frameworks. Linking asylum jurisdiction with the geographic location of EU Member States shapes specific moral and political geographies within the EU. Dublin, like Schengen, can be understood as a tool of internal externalization or the shifting of border control activities from central EU states to its periphery (Cobarrubias et al. 2023: 7). The responsibility of the country to conduct asylum procedures should “motivate” countries at the outskirts of the EU to tighten border controls. The fact that this does not happen, or at least not to the expected extent and with the expected results, leads to another round of blame between North and South, as well as West and East, for incompetence, disinterest, inefficiency, etc. (cf. Rozakou 2017: 44).

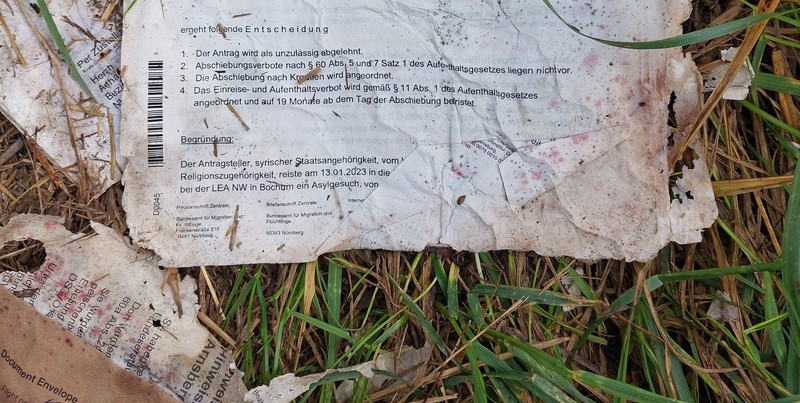

Countries, despite the threat of numerous Dublin deportations and asylum claims—in a manner described by Bernd Kasparek (2016) as a “tacit” complicity or mimetic approach to migrant movements—ignore, tolerate, and even facilitate transit in different ways. Efforts are being made to revise this situation through amendments and enhancements to the already complex and extensive Dublin legislative framework, as well as agreements about “burden-sharing” programs such as relocation or defining monetary compensations for states unwilling to participate, as envisaged in negotiations over the final form of the New Pact on Migration and Asylum. Dublin, as well as these practices, reveals a “Eurocentric view of refugees and asylum seekers as objects of control and/or charitable intervention,” which hinders their abilities of making autonomous decisions, such as choosing a host country (Picozza 2017b: 84). Such Eurocentric understandings, according to some authors (Juss 2013: 310), have parallels with population management in former colonies, from which the majority of asylum seekers originate today. As emphasized by Kasparek, seen from the perspective of migration regime, Dublin can not be reduced to halted or return mobility, but includes disempowering the migrant population and the social practice of exclusionary inclusion (Kasparek 2016: 68). From this perspective, Dublin is recognized as a spatial metonymy, a synonym for taking and erasing fingerprints, for cycles and years of waiting, hiding, fleeing, family separation, deportations of only some family members, empty and full flights organized specifically for this purpose, or regular flights. In other words, Dublin could be understood as a legal fence, an administrative wall between core and peripheral states. Dublin is the statements, decisions, appeals, and responses, piles of documents accumulated over years in personal files that testify with their thickness to the endless labyrinths of Dublin administration.

In a broader sense, Dublin is a metaphor for the production of illegality, deportability, and refugehood within the European Union. Dublin results in forced movements within Europe, which can be said to produce intra-European refugees, if we accept the definition of refugees as forcibly displaced persons (cf. De Genova, Garelli, and Tazzioli 2018: 246). Dublin is a legal framework that keeps asylum seekers in constant uncertainty, interweaving legality and illegality, arrivals and departures, threats of deportation, returns and escapes.

The idea of a safe third country, meaning a country that is neither the country of origin nor the country where the person currently resides, but the country through which someone has arrived (Collinson 1996) is the core idea of Dublin. According to Dublin, asylum seekers who entered the EU through this “safe” country should be returned there. However, not all European countries are absolutely safe, nor safe for everyone, nor in every respect. Therefore, the concept of a safe third country can be labeled as a legal fiction (Juss 2013: 212). Two fundamental Dublin principles mentioned in the literature are also legal fiction (cf. Picozza 2017a: 234). The first is that all signatory states have equal standards of protection, and the same life standards, and the second is that each of them can be entered physically illegally from outside of EU, so that the distribution of asylum burdens can be equal. Asymmetries in power, interests, and means, when it comes to the asylum system, manifest through differences in reception conditions, the number of protections granted, the number of deportations, the labor market, the organization of the health and education systems, as well as states’ interest in accepting refugees.

All countries should participate in uploading fingerprints into Eurodac, just as all asylum seekers should apply for asylum in the country of first entry and give fingerprints there. However, in practice, both states and potential asylum seekers resist these imperatives in various ways. For instance, during the long summer of migration, most countries along the transit route did not register asylum seekers, or at least not consistently and in accordance with the legal framework (Rozakou 2017). States at the external border are sometimes more inclined towards tolerating transit than processing asylum requests, thus in practice subverting Dublin. Survivors rescued at sea who refuse to give fingerprints upon arrival in Lampedusa by collectively burning or otherwise destroying their fingertips, or people on the Balkan route who refuse to apply for asylum even at the cost of another night sleeping rough or pushback, are also examples of resistance to Dublin. There are numerous examples of collective organizing by asylum seekers who are under treat of Dublin. The most known are probably in Germany (e.g., Lampedusa in Hamburg). Recently, there have been ongoing protests in Switzerland and Slovenia against Dublin deportations to Croatia. Dublin has been continuously challenged not only on streets, publicly and covertly, but also in courts across Europe for over a decade, usually focusing on deficiencies in individual countries, starting with Greece. Dublin deportations to Greece were suspended in 2011 following a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights (M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece), and in 2016, in line with the general erosion of protection standards, the European Commission recommended deactivating the suspension. A series of European courts, from Germany to Switzerland, have challenged Dublin returns to Croatia due to the risk of collective expulsions (pushbacks).

While the Balkan corridor was still active, Western European countries, primarily Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, sporadically conducted Dublin deportations to Croatia. In 2016, these deportations became so massive that they were referred to as the “Balkan route reversed” (cf. counter-corridor) Ahmad Shamieh from the outskirts of Damascus was among the thousands awaiting Dublin deportations to Croatia that year. Like many others, he found himself in endless legal and political mazes of deportability (Zorn 2021: 5). Ahmad had been in different countries, constantly moving back and forth. He applied for asylum in Slovenia, but he was entitled to Dublin instead to asylum. Croatia, not Slovenia, was deemed responsible for his asylum request. Appeals followed in various courts, along with protest actions. Ultimately, Ahmad was not deported to Croatia. As Jelka Zorn concludes in her article describing and interpreting Ahmad’s anti-Dublin struggle, if deportation is a site of sovereign enactment, resisting deportation is a struggle against the raw power of the state. Such a struggle requires spaces “defined by practices of autonomy, solidarity and freedom as never given as a substance of rights, but always fought for” (2021: 12). Spaces and communities are essential for this struggle. Ahmad Shamieh and other asylum seekers mobilize communities and constitute themselves as political subjects in the fight for their rights despite the lack of status or basic rights.

30/11/2023

Literature

Cobarrubias, Sebastian, Paolo Cuttitta, Maribel Casas-Cortés, Martin Lemberg-Pedersen, Nora El Qadim, Beste İşleyen, Shoshana Fine, Caterina Giusa i Charles Heller. 2023. „Interventions on the Concept of Externalisation in Migration and Border Studies“. Political Geography 105: 102911.

Collinson, Sarah. 1996. “Visa Requirements, Carrier Sanctions, 'Safe Third Countries' and 'Readmission'. The Development of an Asylum 'Buffer Zone' in Europe”. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 21/1: 76-90.

De Genova, Nicholas, Glenda Garelli and Martina Tazzioli. 2018. “Autonomy of Asylum? The Autonomy of Migration Undoing the Refugee Crisis Script”. The South Atlantic Quarterly 117: 239-265.

Fontanari, Elena. 2018. Lives in Transit. An Ethnographic Study of Refugees’ Subjectivity across European Borders. London and New York: Routledge.

Juss, Satvinder S. 2013. “The Post-Colonial Refugee, Dublin II, and the End of Non-Refoulement”. International Journal on Minority and Group Rights 20: 307-335.

Kasparek, Bernd. 2016. “Complementing Schengen. The Dublin System and the European Border and Migration Regime”. In Migration Policy and Practice. Migration, Diasporas and Citizenship. Harald Bauder and Christian Matheis, eds. Palgrave Macmillan: New York, 59-78.

Kuster, Brigitta and Tsianos, Vasilis. 2016. „How to Liquefy a Body on the Move. Eurodac and the Making of the European Digital Border”. In EU Borders and Shifting Internal Security. Technology, Externalization and Accountability. Raphael Bossong and Helena Carrapico, eds. Cham: Springer, 45-63.

Picozza, Fiorenza. 2017a. „Dubliners. Unthinking Displacement, Illegality, and Refugeeness within Europe’s Geographies of Asylum”. In The Borders of "Europe". Autonomy of Migration, Tactics of Bordering. Nicholas De Genova, ed. Durham: Duke University Press, 233-254.

Picozza, Fiorenza. 2017b. “Dublin on the Move. Transit and Mobility across Europe’s Geographies of Asylum”. movements. Journal for Critical Migration and Border Regime Studies 3/1: 71-88.

Rozakou, Katerina. 2017. „Nonrecording the “European refugee crisis” in Greece. Navigating through Irregular Bureaucracy“. Focaal 77: 36-49.

Vavoula, Niovi. 2015. „The Recast Eurodac Regulation. Are Asylum Seekers Treated as Suspected Criminals?“. In Seeking Asylum in the European Union. Selected Protection Issues Raised by the Second Phase of the Common European Asylum System. Céline Bauloz, Meltem Ineli-Ciger, Sarah Singer and Vladislava Stoyanova eds. Leiden: Brill, 247-275.

Zorn, Jelka. 2021. "The Case of Ahmad Shamieh’s Campaign against Dublin Deportation. Embodiment of Political Violence and Community Care". Social Sciences 10/5: 154.