Porin

Officially, The Reception Center for Asylum Seekers in Zagreb, colloquially and widely known as Porin, is the larger of the two reception centers of this type in Croatia, and can accommodate up to 600 people (the other, much smaller center, with a capacity of 100 people, is located in Kutina). The center was opened in 2011, and its vernacular name Porin comes from the hotel of the same name which operated in this building until the center was opened. It is under the authority of the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Croatia, with the Croatian Red Cross acting as the main partner of the Ministry in the day-to-day management of the center. Porin is an open-type reception center, which means that people staying there with the status of asylum seekers can leave and enter it relatively freely, while respecting the curfew prohibiting exits and entries between 11 pm and 6 am. This, among other things, distinguishes it from detention centers or camps where people on the move do not have the option to leave. On the other hand, its highly administrative and security structure and organization, the fact that only persons with the status of asylum seekers are allowed to stay, as well as the fact that the building possesses a relatively adequate infrastructure for housing people (e.g. rooms with bathrooms), and offers organized meals, set it apart it from “wild camps”, such as Vučjak in Bihać in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The number of people staying in the center, as well as their countries of origin, vary depending on global geopolitical events and the routes that are passable to people on the move. Porin briefly reached its maximum capacity after the closure of the Balkan corridor in the fall of 2016, while in recent years, it has mostly been operating significantly below its full capacity. Before the long summer of migration in 2015, seekers often came from Africa, while the number of applicants from Asia (primarily Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and Iran) has increased significantly since 2015. After the breakout of the war in Ukraine, it is interesting to note that people who fled Ukraine in 2022 were not placed in Porin (different accommodation facilities, different statuses, rights and acceptance conditions were provided for them), while on the other hand, people coming from Russia stayed in Porin with the status of asylum seekers.

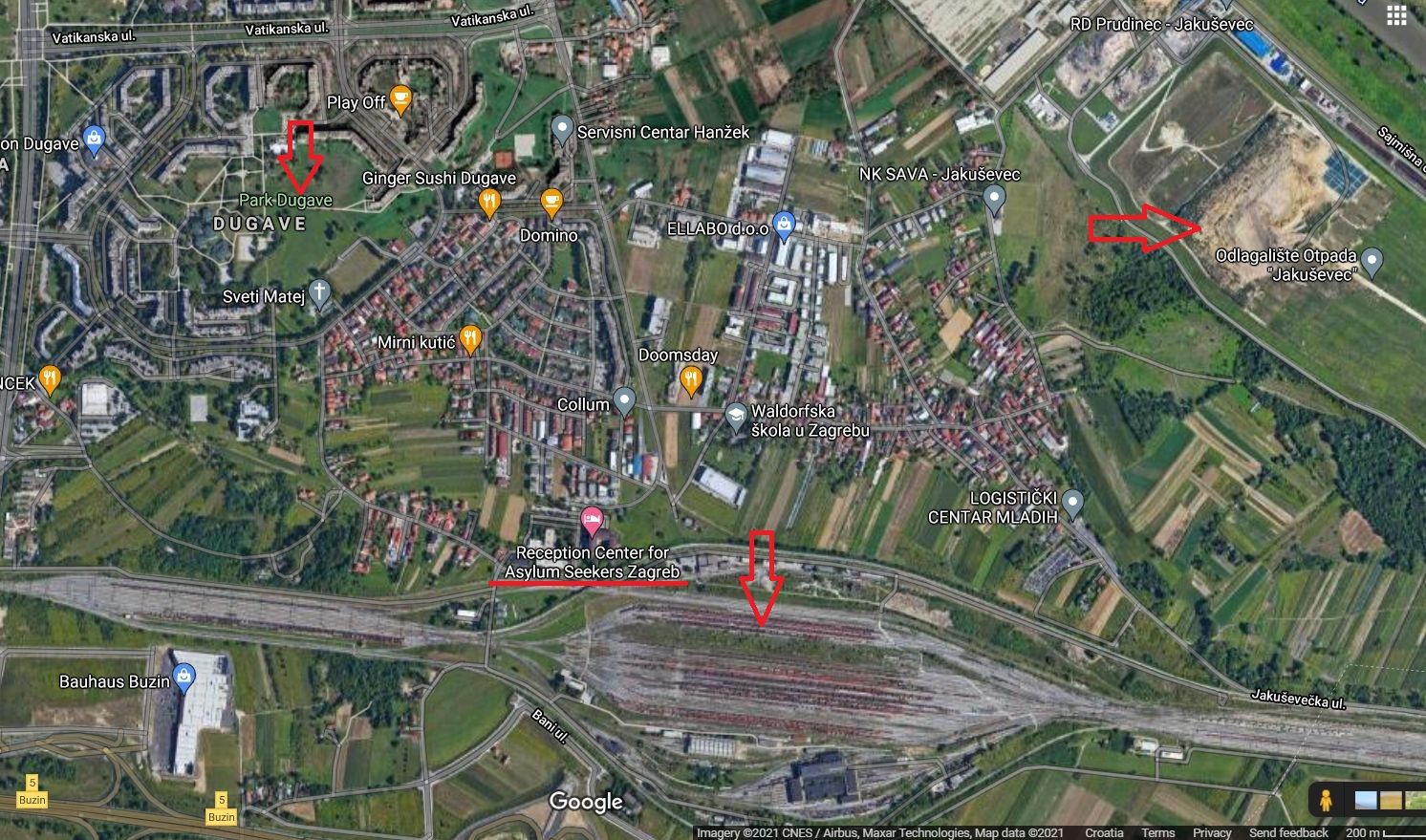

Porin is located on the southeastern edge of Zagreb and administratively belongs to the Hrelić Local Board, although its residents, as well as employees, volunteers, representatives of non-governmental organizations, activists and other actors, are more likely to place it in the adjacent neighborhood of Dugave on their mental map of Zagreb. The center is located on the edge of the residential part of the neighborhood: it is surrounded by smaller residential buildings on its north side, while the Zagreb marshalling yard stretches along the southern end of the shelter. The Prudinec landfill in Jakuševac is located a little further, around three kilometers to the east of Porin (cf. garbage). In addition to defining it spatially, these characteristics are also important for the experience of the people it houses, so the first associations of Porin are often noise and waking up during the night because of the marshalling yard and the stench that often, especially during the warmer months, wafts to the center from Jakuševac.

Another physical characteristic strongly influences impressions of Porin. A barbed wire fence was erected around the center in March 2020. The Ministry of the Interior offered the explanation that the fence was erected solely to protect the people housed in Porin, especially children, from traffic, since the main entrance/exit is located next to a road and a parking lot. However, although the fence did not change the characteristics of Porin as an open center, the erection itself, and especially the period in which its construction took place, in March 2020, when the coronavirus epidemic in the Republic of Croatia was declared and the lockdown was imposed, had a strong impact on the impressions of people who were situated in Porin at that time, and some began to perceive it more like a prison.

Assessments on the perception of (in)security and risk have always been part of everyday life in Porin. On the one hand, we are talking about the significant security infrastructure and techniques of the Ministry of the Interior (Pozniak and Petrović 2014). For example, in addition to the aforementioned fence, a video surveillance system has been set up, iron grates are placed on the staircase between the floors (which are generally completely open, and would be locked in the event of a riot), and the entry/exit of residents from the building is recorded with magnetic cards. On the other hand, the perception of risk and insecurity also comes from outside, mostly from people who live near the center. While residents of the Dugave neighborhood generally seldom interact with people housed in Porin (Brnardić et al. 2015), they often perceive them as a threat (Pozniak and Petrović 2014), and their attitudes towards the asylum seekers from Porin often vary between compassion and concern, and fear and xenophobia (Petričević 2022).

The length of stay in Porin varies greatly and depends on many factors. Many leave Porin after a few days or weeks and do not wait for their claims in Croatia to be resolved. For others, who wait for a decision on the approval or rejection of asylum, the stay lasts significantly longer (although its duration is always very indefinite), anywhere between ten months to three or more years in some cases.

Waiting, more precisely, waiting for an unknown amount of time, is one of the most salient characteristics of life in Porin, much like other facilities with similar functions (Grubiša 2022; Altin and Minca 2017; Michalon 2013). People in Porin know that the center is only a temporary station, regardless of the conditions and with what legally assigned statuses they will leave, but they do not know how long this temporary stay will last. Since it often lasts longer than a year, they frequently describe their stay in Porin as a period of being stuck in time (Jefferson, Turner and Jensen 2019) or as a feeling of “hanging” between two lives, as one of the interviewees for my doctoral research described it after living for more than three years in Porin:

Sometimes, it [Porin] makes one feel like you are in prison. And now that we are in the apartment, I feel the difference between while we were there and now. I feel like, like I am now in Croatia, actually. To be honest. There in Porin, I felt like I’m still hanging. Like our life is not complete, and we are not free people. Like we are stuck in something!

Although waiting is the main fixture in the lives of Porin’s residents, it should not be written off as passive space and time. Its residents remain active actors, adapting to new circumstances, resisting having their identities reduced to passive asylum seekers, and, despite numerous structural limitations, they strive to ensure meaningful everyday lives for themselves and their families (Fontanari 2019; Dudley 2011). In the context of life in Porin, this is manifested, among other things, in the frequent practice of arranging rooms according to their needs and wishes (bringing in new furniture and reorganizing the rooms, painting and decorating the walls...) which transforms the cold and hostile spaces devoid of meaning into their own, filled places with multiple meanings, which some even call home. Porin, therefore, is not a mere non-place (Augé 2001), but a continuously constructed, negotiated and disputed place. Its physical space and infrastructure, written and unwritten rules and norms, as well as its employees, but also its inhabitants, all actively participate in its transformations, social production and construction (Grubiša 2022).

5/2/2023

Literature

Altin, Roberta and Claudio Minca. 2017. „The Ambivalent Camp. Mobility and Excess in a Quasicarceral Italian Asylum Seekers Hospitality Centre“. In Carceral Mobilities. Interrogating Movement in Incarceration. Jennifer Turner and Kimberley Peters, eds. London and New York: Routledge, 30-43.

Auge, Marc. 2001. Nemjesta. Uvod u moguću antropologiju supermoderniteta. Karlovac: Naklada Društva arhitekata, građevinara i geodeta. Translate Vlatka Valentić.

Brnardić, Sunčica, Emina Bužinkić, Mitre Georgiev, Julija Kranjec, Sara Lalić, Cvijeta Senta and Tea Vidović. 2015. Izazovi integracije – izvještaj za 2014. godinu. Zagreb: Centar za mirovne studije.

Dudley, Sandra. 2011. „Feeling at Home. Producing and Consuming Things in Karenni Refugee Camps on The Thai-Burma Border“. Population, Space and Place 17: 742-755.

Fontanari, Elena. 2019. Lives in Transit. An Ethnographic Study of Refugees’ Subjectivity across European Borders. London: Routledge.

Grubiša, Iva. 2022. „From Prison to Refuge and Back. The Interplay of Imprisonment and Creating a Sense of Home in the Reception Center for Asylum Seekers“. Journal of Borderlands Studies.

Jefferson, Andrew, Simon Turner and Steffen Jensen. 2019. „Introduction. On Stuckness and Sites of Confinement“. Ethnos. Journal of Anthropology 84/1: 1-13.

Michalon, Bénédicte. 2013. „Mobility and Power in Detention. The Management of Internal Movement and Governmental Mobility in Romania“. In Carceral Spaces. Mobility and Agency in Imprisonment and Migrant Detention. Dominique Moran, Nick Gill i Deirdre Conlon, eds. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate, 37-55.

Petričević, Igor. 2022. Beyond Transit. Precarious Emplacement and the Weavering Reception of Migrants in the City of Zagreb. Dissertation. Stockholm University.

Pozniak, Romana and Duško Petrović. 2014. „Tražitelji azila kao prijetenja“. Studia ethnologica Croatica 26: 47-72.