Mobile Phone

A few hours after I settled in Bihać in December 2020, in the attic apartment of a house on the outskirts of the city with six other international volunteers from a pro-migrant collective I had just joined (cf. distro), someone loudly knocked on the door. Due to the strict control of Croatian borders and the normalized practice of pushbacks, people on the move were forced to avoid populated areas and travel clandestinely through forests and mountains while passing through the Croatian section of the Balkan route. Their daily lives were completely invisible to the general public. Images with criminalizing effects were prevalent among the few media representations of migrations during that period, in line with national and European securitization policies. One photograph particularly stuck in my memory from a news piece about the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ new surveillance equipment intended to “prevent illegal crossings by migrants.” The nighttime photograph showed a group of eight people, zoomed in from a great distance, like prey. The distant, targeted people (captured) in motion across an abstract, open space were tightly huddled together and completely depersonalized, reduced to white outlines on a black background. Along with demonstrating new surveillance power and the extreme objectification of people on the move, the image also reinforced the illusion of their separation—as if they were in a dimension parallel to the everyday life of news readers who were learning about the hunt for “illegal migrants.”

View of Plješivica. Bihać, January 2021. Photo: Bojan Mucko

When I heard the knock, I was in the hallway, closest to the door, so I opened it spontaneously. I saw six young men in their twenties and thirties standing in the dark in front of the door, on the staircase with a view of the mountainous outlines of the monumental Plješivica behind them. The one with the widest smile among them was the first to extend his hand and greet me with: “Hello brother, how are you doing?”. That was when I met Javed, Raja, Bilal, Usman, and others from one of the improvised tent squats in the area. They lived beyond the reach of the city’s infrastructure, in a field at the foot of Plješivica that stretched all the way to our house, and like every few days, they had come for their phones. They charged them in a small room near the entrance, on a shelf amidst a sea of power cables. Our apartment was their nearest access point to electricity, and the volunteers helped them with charging even though gatherings in the yard were prohibited (as one of the anti-pandemic measures active at that time). Just a few kilometers further north, on the other side of the Croatian border, such an encounter would have been practically unimaginable to me at the end of 2020.

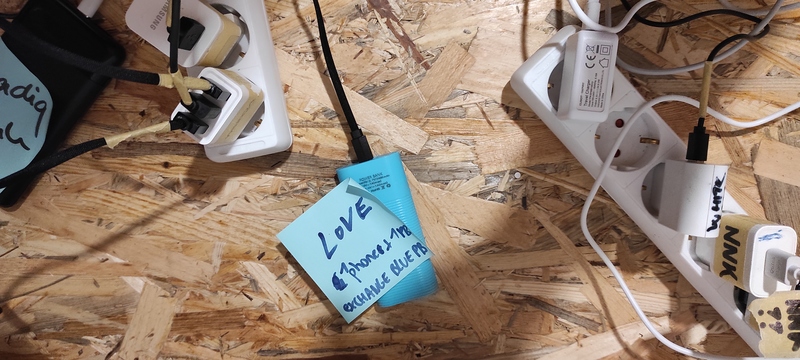

Phone charging. Bihać, winter 2021. Photo: Bojan Mucko

Unlike the faceless outlines targeted by thermal imaging cameras, the young men, just like the newsreaders, were quite individualized, each marked by their own personal contexts, biographies, and projections of the future. The mobile phones they came to collect were, to me, like a bridge from the world of media representations to the world of “field” reality and neighborly interactions. And those same mobile phones were essential tools, necessary for navigating their daily challenges.

|

|

Power banks protected with improvised means. Bihać, winter 2021. Photo: Bojan Mucko

Elisabeth Eide’s interlocutors in her research conducted in Norway with asylum seekers noted that the most valuable part of their mobile possessions was the mobile phone (2020: 72). Eide interprets the smartphone as a basic logistical tool for confronting the precarious living conditions of people on the move, analytically dividing general precariousness into three phases (2020: 77). The first phase relates to the period before the journey, the context from which individuals flee or leave. The second phase involves the journey to European destinations, and the third phase pertains to life upon arrival in the new environment. In the pre-departure phase, the mobile phone primarily serves as a communication and organizational tool for planning the route, purchasing tickets for various means of transport, and communicating with people close to them, as well as with smugglers, who are often reached through advertisements on social media. During the journey itself, these device functions are further refined to improve safety in unpredictable situations in unfamiliar terrain (Eide 2020: 71). Offline map applications and GPS navigation are used in choosing the safest routes, helping to avoid natural dangers and tactically outsmart actors of the regulatory and repressive apparatus of the migration control regime. Upon reaching a European destination, the functions of the mobile phone shift towards exploring the new social environment, obtaining information about the national asylum system and current administrative processes, mastering a new language, and establishing new and maintaining old contacts. Throughout all stages of the journey, the mobile phone also functions as a personalized archive of memories stored in various media, providing access to identity-important content such as music or films, and generally to the (media-mediated) information through which individuals acquire transnational knowledge and competencies (Eide 2020: 78).

Tea in a squat with an Afghani playlist. Bihać, winter 2021. Photo: Bojan Mucko

Hundreds of groups and individuals stranded in Bihać, outside official camps, in dilapidated buildings and tent shelters, like Javed and his friends, found various ways to charge their mobile phones. Their options were generally limited to using outlets available in public spaces such as bus stations, cafes, shops, and shopping centers. Like my housemates, and many other more or less visible local and international helpers, charged their phones in their hallways and living rooms out of solidarity. Our shelf became increasingly complex: new power cables and outlets sprouted, and we labeled the constantly changing phones with names for easier identification. As the friendships between the volunteers and the people from the squats deepened daily, the name labels sometimes evolved into a form of communication – they became small greeting notes or cards wishing luck for the game, handed over along with the fully charged phone.

Personalized messages with the charging phones. Bihać, winter 2021. Photo: Bojan Mucko

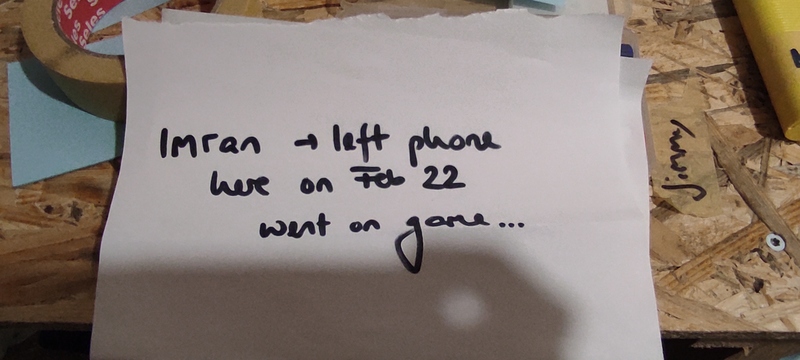

However, when the game through Croatia would end with a pushback, people would mostly return without their mobile phones. It was known that Croatian police regularly either stole or destroyed mobile phones, with their selection criteria being market-based. As recounted by numerous interlocutors based on their experiences – an expensive phone would go directly into the police officer’s pocket (gesture of inserting an object with the right hand into the left inner pocket of a jacket), and a cheap one under the police boot (gesture of smashing a device with the sole of the boot). Whether it was theft or destruction, for people on the move, it meant the same thing – the loss of their most valuable personal belonging necessary for navigating their precarious everyday life at all stages of the journey. For this very reason – knowing that there were high chances of another pushback, individuals traveling in groups began leaving their phones and other small electronic devices with us for safekeeping before embarking on the game, despite the reduced number of phones making the journey more difficult for the group. If the journey to Europe was successful, the phones left in Bihać would find new owners (cf. mobile commons and autonomy of migration), but if it ended with a pushback, they would be waiting on the shelf. After days or weeks of wandering through forests and encounters with the police, which often (along with physical and psychological violence) involved the confiscation or destruction of all movable property, the mobile phone provided the necessary tools to reconnect with the world from which they were being pushed out with every pushback: contacts with family and friends, apps, playlists, movies, personal photos, and videos preserved from police brutality on a palm-sized device (along with Bluetooth speakers charged for a party).

Note. Bihać, winter 2021. Photo: Bojan Mucko

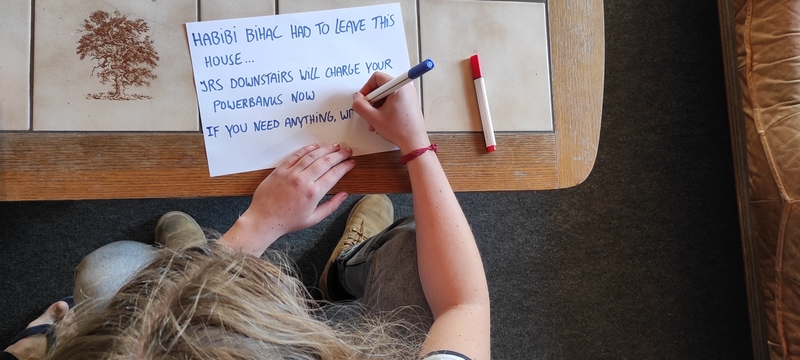

When the volunteer collective was moving out of the attic apartment on the outskirts of the city, we arranged with the international humanitarian organization, whose offices were on the ground floor of the same house, to take over the practice of charging mobile phones. We left a message with new instructions for our friends on the outside of the door they were already used to knocking on. The organization on the ground floor, in line with their more formal mode of operation compared to the collective, decided to build a self-service charging station – with lockers under lock and key on the ground floor, on the exterior staircase of the house. With the introduction of keys, the poetic notes with good wishes attached to the phones disappeared as well.

Goodbye letter from the volunteers. Bihać, spring 2021. Photo: Bojan Mucko

Although smartphones have been in widespread use since the second half of the 2000s, research into the role of mobile phones in refugee daily life has gained significance with the so-called “Syrian refugee crisis” and the broader mass movement of people towards Europe during 2015 and 2016, as these transcontinental migrations of such proportions are the first to occur in the digital age (cf. Alencar 2020: 9). The democratization of GPS technology and the possibility of mobile access to social networks and various other applications have enabled greater autonomy for people on the move from smuggling structures (Alencar 2020: 4). Alongside these positive aspects, the use of mobile phones also brings a number of ambivalences. As Amanda Alencar points out, different border control mechanisms, such as satellite technology, drones, and motion detectors, rely precisely on tracking mobile phones: “GPS apps can be used by state officials, traffickers, and smugglers to track refugees’ movements, meaning that the same tools that some have cited as critical to their journey may also make them vulnerable to arrest and abduction” (2023).

|

|

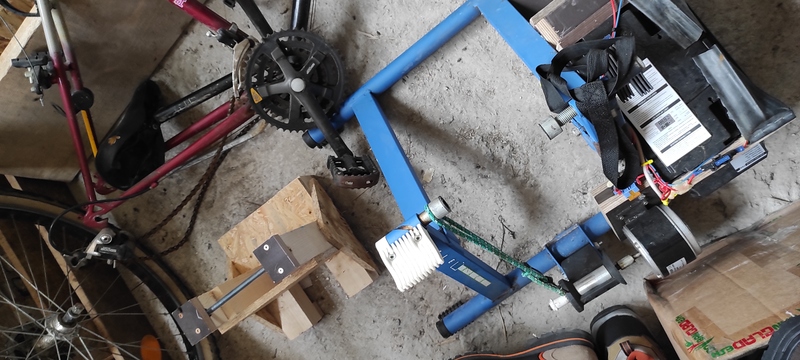

Donation from Luxembourg: machine for phone charging powered by legs. Una-Sana canton, summer 2021. Photo: Bojan Mucko

Mobile phones are thus relied upon by differently positioned and mutually antagonistic actors within the migration regime marked by radical oppositions. While the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), for example, advocates for the digital inclusion of people on the move, enabling their integration into the social life of their destination (at least nominally), while police forces regularly destroy or steal the very tools crucial for this type of inclusion. On several occasions in the field, I even heard rumors about two Croatian police officers who allegedly returned stolen phones into circulation. Supposedly, they sold bags full of stolen devices to resellers at the Bihać market. There, on the outskirts of the city, by the bypass near the railway tracks, the phones were then bought back by those who needed them the most—the original owners from whom they had been stolen.

Nina Khamsy conducts research on the role of smartphones in the everyday lives of people from Afghanistan navigating the Balkan route. She views participants in social research as “part of a multidimensional field which is now both multi-sited and multi-modal” (Khamsy 2022: 267). Here, multimodality refers primarily to the intertwining of virtual and physical networks and spaces, as well as the spontaneous production and exchange of audiovisual content during social interactions in the field. Khamsy warns that the normalization of violence forces us to constantly reevaluate our role in “knowledge production in this (mine)field” (Khamsy 2022: 267). In my own multimodal ethnographic research on migration regimes, focusing on the coexistence of people on the move and international volunteers, I also relied on my phone as a primary tool for navigating a daily life marked by the criminalization of solidarity and normalized violence. In an environment that demanded constant discretion, this handy, pocket-sized device replaced a voice recorder, camera, map, laptop, pen, and notebook.

For people on the move, trapped not only on the Balkan route but also in camps around the world, living in conditions whose brutality is hidden by local authorities from the international public, the mobile phone takes on additional significance—it becomes a tool of citizen journalism (cf. Allan 2013) which opens a communication channel to the world from below, from within the camp itself. Sally Hayden conveys the testimonies of silenced detainees in the notorious Libyan camp Dhar-el-Jebel, who speak about the invaluable role of mobile phones carefully hidden from the guards: “Receiving messages from journalists and activists outside was ‘like a candle in the night’” (2022). Announcements of deaths concealed in the camp, published on social networks, were often the first information about the fatalities for the families of the deceased. The world-famous book No Friend but the Mountains, written by Kurdish-Iranian journalist and activist Behrouz Boochani during his detention in Australian custody, was also composed through WhatsApp correspondence with a friend outside the camp.

In one of the field episodes, a mobile phone enabled me to contact hunger strikers in the recently burned Lipa camp, resulting in audio-visual materials consolidated under the terms Protest in Lipa and WhatsApp from Lipa. On other occasions, I used my mobile phone to record diary notes from the gatherings with the people whose phones we were charging (cf. party in the Afghan squat).

29/12/2023

Literature

Alencar, Amanda. 2020. “Mobile Communication and Refugees. An Analytical Review of Academic Literature”. Sociology Compass 14: 8.

Alencar, Amanda. 2023. “Technology Can Be Transformative for Refugees, but It Can Also Hold Them Back”. Migration Policy Institute.

Allan, Stuart. 2013. Citizen Witnessing. Key Concepts in Journalism. Cambridge and Malden: Polity Press.

Eide, Elisabeth. 2020. “Mobile Flight. Refugees and the Importance of Cell Phones”. Nordic Journal of Migration Research 10/2: 67-81.

Khamsy, Nina. 2022. “Mobile Phones on Mobile Fields. Co-producing Knowledge about Migration and Violence”. Antropologia Pubblica 8/1: 261-268.

Hayden, Sally. 2022. “For Refugees in Detention Camps, Smartphones Are a Lifeline”. Wired.