Lipa Protest

The Lipa camp is a “reception center” for people on the move, opened in the spring of 2020 in the Una-Sana Canton during the COVID-19 pandemic. The camp was erected and operationalized through the coordination of cantonal and state structures of Bosnia and Herzegovina and their international partners – the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), with funding primarily from the European Commission. Initially, the management of the camp was entrusted to the IOM. It is located in an isolated area on the edge of the Una National Park, near a village emptied during the war in the 1990s, after which the camp was named. At the opening of the camp, the head of the canton presented it as the result of a two-year effort “to relocate migrants from the urban parts of Bihać, the municipality of Velika Kladuša, and other municipalities and cities to uninhabited areas.” However, local activists emphasized that these relocations were carried out forcibly and that such ghettoization of people on the move was a consequence of anti-migrant policies concealed as anti-pandemic measures (cf. Ahmetašević 2020). Additionally, the period of camp management from April to December 2020 was marked by numerous contentious arguments between local authorities and the IOM, on the one hand, and cantonal and state levels of government, on the other. The camp was constructed as a temporary, tent solution in a location beyond the reach of water and electrical networks, and the IOM expected infrastructural interventions from local authorities which would facilitate its transformation from a tent camp into a container camp equipped for the winter conditions in the middle of the forest.

Given that the investments were not realized by winter, the international administration of the IOM decided to hand over responsibility to local authorities and dismantle the camp. Consequently, on 20 December 2020, Lipa was temporarily closed despite the lack of any sustainable alternative accommodation for the people who had been residing there. The main international actor for refugees in Bosnia and Herzegovina essentially left around 1,200 people to fend for themselves in the forest, approximately a six-hour walk from urban infrastructure. As columns of people left the camp, carrying all their belongings in backpacks and plastic bags, the camp was already being dismantled. Amid these events, a fire broke out, quickly engulfing the tent section of the camp. In the following days, authorities demonstrated how unprepared they were to deal with the situation. Plans to relocate the residents to either old locations (Bira camp in Bihać) or new ones (the former barracks in Bradina) were thwarted by anti-migrant protests from the local population. At one point, former camp residents were loaded onto about twenty buses under police supervision. The buses, due to protests at the destination points, never departed. Consequently, people were forced to spend the night in the buses. After that, without any real solution, they were once again left to face the elements. Many returned to the partially dismantled and partially burned camp, starting to squat in the remnants of the fire-damaged administrative and hygiene containers. On the first day of 2021, some of the residents trapped in the post-apocalyptic ruins of the camp organized a hunger strike.

These events occurred during the time when I joined the humanitarian work of a pro-migrant international collective operating in Bihać (cf. distro). When the protest began, I was in Zagreb. An international volunteer, who had been in Bihać for months and whom I had met as a member of the collective, contacted me with a proposal to connect me with one of the people on strike in the camp, who wanted to share his perspective with the media. After a brief exchange of messages, we arranged a video call for the next morning.

My phone rang while I was in the office. I answered the WhatsApp video call, expecting to see the face of my interlocutor on the other side. Instead, the screen was filled with the faces and bodies of a mass of men standing tightly packed in front of white containers, looking straight at me. I turned on the phone’s speaker, and the loud chanting of the strikers filled the narrow office space. First, I heard the voice of someone rhythmically and loudly shouting a sentence:

EU save our lives!

It was immediately echoed by the entire collective following the same rhythm:

EU save our lives!

The chanting continued in the same manner for several minutes:

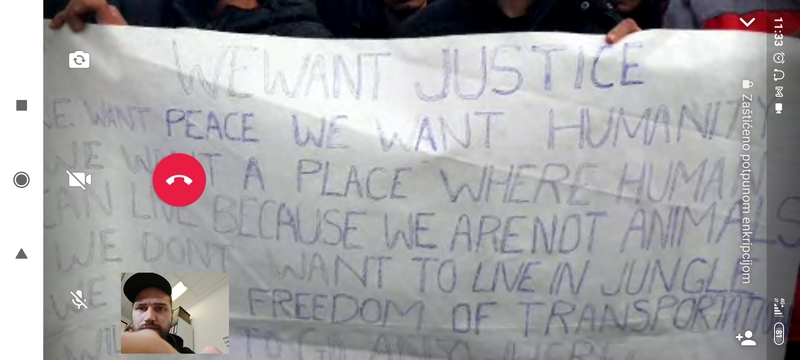

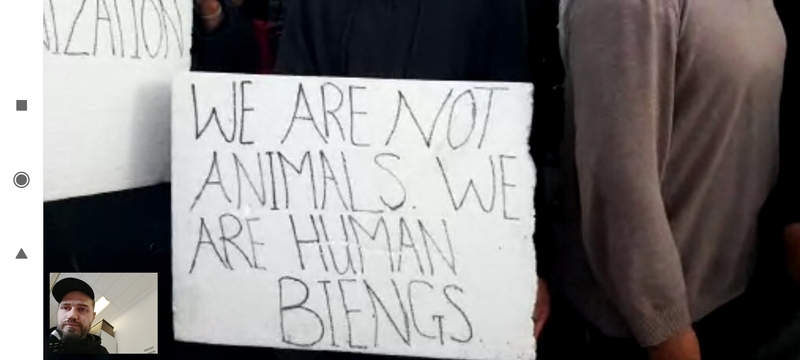

We want justice! We want justice! We want justice! We want justice! We want justice! We want justice! We want justice! We want justice! We want freedom! We want freedom! We don't want food, we want justice! We don't want food, we want justice! EU save our lives! EU save our lives! EU save our lives! EU save our lives! EU save our lives! EU save our lives! We want justice! We want justice! We want justice! We want justice! We want justice! We want justice! We want peace! We want peace! We want peace! We want peace! We want peace! We want peace! We want peace! We want peace! We don't want this place! We don't want this place! We don't want this place! We don't want this place! We don't want this place! We don't want this place! We don't want this place! We don't want this place! EU save our lives! EU save our lives! EU save our lives! EU save our lives!

During this time, as the office resonated with the rhythm of the protest, I sat at my desk, holding the screen filled with the protesting crowd in my hands. Since I was unprepared for the situation but felt the need to document the events I was witnessing, I had to improvise. Every few seconds during the call, I would take a screenshot of my phone.

In the lower left corner of the screenshot, right in line with the banners, there was an open window showing my face with the office in the background.

Two spatial perspectives are thus present in the same picture. The view of the camp is captured by the rear camera of the phone in Lipa, while the view of the office is captured by the front camera of my phone. Consequently, the picture encompasses two different dimensions of the migration regime: the protest dimension and the academic dimension.

The video call abruptly disconnected, without warning. I felt as though I had been struck square in the face – dislocated, privileged, addressed, unprepared, useless, claustrophobic, and crumpled.

I typed a message thanking them for the call and expressing support for the protest. The reply I received read:

Just now the policeman saw me so I cut off the call.

We continued messaging and agreed to try to speak again later when my interlocutor could talk. Based on the conversation that took place half an hour later, video materials were created and published in the note “WhatsApp from Lipa.” These video materials depict the daily life of people on the move trapped in the post-apocalyptic ruins of the camp from an insider’s perspective and also convey the political demands of the hunger strikers directed at the European Union. The hunger strike ended on 5 January 2021, and a new container camp equipped for winter conditions was officially opened at the same location a whole eleven months after the fire, in November 2021.

12/12/2023

Literature

Ahmetašević, Nidžara. 2020. Ljudi u pokretu bez ljudskih prava. Sarajevo: The Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.