Madina Hussiny

According to Aleksandra, a volunteer in the refugee camp in Sofia, where Madina Hussiny (Hosseini, Husseni), a girl from Afghanistan who was at most five or six years old when she died on the Croatian-Serbian border during the pushback from Croatia, lived for several months in 2016 with her large family: The biography of someone who hasn’t even lived their life can’t actually be written. The milestones of life’s journey, intimate and socially recognized struggles and achievements, everything that makes up the essence of a biography, are actually the privilege of those who had the opportunity to live, grow up, grow old. Madina had no such chance. Madina was at most five or six years old when she died on the Croatian-Serbian border at the end of 2017.

The biography that follows covers only the last stops of Madina’s journey from Afghanistan, through Iran and Turkey to Europe. In addition to the summary of events of the night in which she tragically died, the biography contains the impressions she left on employees and volunteers in the facilities for collective accommodation on the peripheries of the European Union. It is based on information from the media, court rulings and reports, as well as interviews conducted in 2021 with Aleksandra, Andrijana, Jovana, Francesca, Katerina, Margarita and Silvia who met Madina in Bulgaria and Serbia, in the camps where, according to the interviews quoted here in italics, bed sheets can be a luxury, and torn furniture comes standard.

They remember Madina as tiny, really tiny, small, with a big head and large, curious eyes that were something really special. They remember her as very beautiful, very sweet, with a slightly round face, chubby and with a big smile and wonderful eyes, with curly, very curly hair, quite black and quite thick, and a skin that was darker, olive, and with a Sherpa hairstyle, which slowly grew out. They emphasize Madina’s special, sweet voice, similar to the voice of a very small child who does not yet know how to pronounce all the words. They remember her as an extremely cheerful girl who radiated happiness. As summed up by Jovana, who met Madina at the camp in Bogovađa, Serbia: It’s as if she carried some sort of joy. She stood out with that kind of joy, and just by being in a room she changed its atmosphere. Aleksandra specifically remembered how disappointed and unhappy Madina was when she couldn’t go on a trip with the other children from the camp because she was too young. Silvija and Francesca, who saw her every day at the camp in Bogovađa, remember Madina’s pride and happiness when she found some kittens, but also the sadness and disappointment she felt because she could not keep them.

Aleksandra, as well as Slivia and Francesca to a certain extent, remember that Madina was inseparable from her slightly older sister, and that volunteers and employees often confused them for one another, because the two of them looked alike, with the same hair color, the same hairstyle, similar height and build. Andrijana, who occasionally came to the camp in Bogovađa, primarily remembers Madina in the company of her younger brother, who also looked a lot like her, and they were close in age as well. She remembers how she took him by the hand and imitated the way adults take care of children, she took his hand, then started talking as if she was warning him about something, like she was scolding him.

Madina, according to our interlocutors’ memories of her, was always in a group of other children of a similar age, with whom, in the words of Jovana, she played around the camp. Sometimes she used to hang out with them in front of the classroom doors or on the windows in the camp in Sofia, waiting for the arrival of volunteers, calling them: Teacher! Teacher! or We are here! We want to go to medresa, medresa! In Bogovađa, they also used to yell out: Caritas! Caritas! because of the words printed on the volunteers’ T-shirts. Silvia jokingly states that Madina was the worst child of all the children there, of all the little rascals, as she called them. She was impossible to deal with and unbearable. She didn't follow any rules, because she’s very small and very cute, so it goes without saying that she can do whatever she wants. In short, Madina was very active, restless, hyperactive, always running and jumping, she was generally delighted with physical contact, even ready for physical confrontations with other children.

She always wanted to participate in everything, in all activities in the camp. In addition to some Bulgarian and Serbian, she also learned English, which, as Francesca summed up, she could follow, but of course she didn’t speak very well. Francesca recalls: How she talks to us, a kind of child-like English, but English. The famous photo of Madina shown below was taken after one such activity at the camp in Bogovađa, with her looking straight into our eyes, playfully sticking out her tongue, arms and body in motion. In that photo, Madina is wearing her black Star Wars T-shirt and was photographed by Silvia on a sunny, summer day after a water coloring workshop attended by many children. Francesca recollects how she took them all to wash their hands on the ground floor, to a shared bathroom and toilet. All of them were dirty and I know the photo was taken at the moment when they all came out of that toilet together. Madina, as Silvija remembers, simply ran out, along with two other children she always spent time with, the same two she was with when she found the kittens.

In the camp in Sofia, Madina socialized with other children her age every day and in the classroom which was always quite noisy. About twenty children were usually in the classroom, and Margarita and Katerina remember that Madina especially loved the dressing room corner, where she would dress up as a princess. Aleksandra also remembers Madina in that little corner, in a very big princess dress. It wasn’t meant for her age. It was very big. She could barely walk in it. It piled up under her feet, but she was happy and kept on saying: Teacher, teacher. She also mentions that Madina loved dolls. And reading. There was a book, Shark in the Park by the British children’s writer Nick Sharatt, which Aleksandra read to the children every day, and they loved to repeat after her. Madina also liked to listen to her read the book and repeat after her. The classroom was a place for play, drawing, singing. This is where Madina probably drew the colorful hearts on the messages for Bulgarian citizens that Margarita and other volunteers distributed in Sofia on World Refugee Day in 2016.

Aleksandra remembers Madina in a purple jacket that was big for her, too big for her, always unbuttoned. She was always running around in that jacket that was always unbuttoned. The photos at the beginning of the video about the organization of the camp in Sofia show Madina in such a jacket around the one minute mark, with a hood over her head and a big scarf around her neck, the way she was described in interviews: small, with wide-open eyes full of questions. Jovana, who occasionally came to Bogovađa, also remembers Madina in a cyclamen-colored coat and in general in those kinds of colors she wore. Jovana, however, also remembers that same coat, jacket covered Madina’s dead body when they returned it to her parents just like that, so cruelly, harshly. When Francesca saw Madina for the last time, at the camp in Belgrade where the family was getting ready for the game, Madina was wearing that pink jacket, like in that photo that you sometimes see on the Internet. I think it might be the last photo of her, Francesca concludes.

Madina Hussiny, Serbia, winter 2017. Photo: unknown author

Madina went on the game on November 21, 2017, with her mother and five siblings. An hour after they clandestinely crossed the border between Serbia and Croatia in the afternoon, they were intercepted by the police. Madina’s mother, as she stated in the complaint she sent to the ombudswoman through Doctors Without Borders, asked the Croatian police for asylum for herself and her underage children. However, they told her that they had to return to Serbia. They told them to come to Croatia again next month. The mother then started begging the policemen to let them at least spend the night in Croatia, because the children were exhausted, but they ignored her pleas. After some time, a police vehicle arrived and transported them to the border, to a place next to the railway line near Tovarnik, which at the time was already known as the place where the Croatian police bring people they pushed back to Serbia. The policemen then ordered them to go back to Serbia, to Šid by following the railway line. Shortly thereafter, the train that knocked Madina down came. The ambulance doctors who arrived at the railway station in Tovarnik, where the police brought Madina after the accident, could only declare Madina’s death at twenty-one hours and ten minutes. Madina’s body was kept in Croatia, while the family was deported to Serbia the same night. The body was subsequently sent to Serbia and handed over to the family. Madina was buried in Šid, where she still rests to this day.

The responsibility for Madina’s death was investigated by the Ombudswoman, the State Attorney Office, at the Municipal Court in Vukovar, the County Court in Osijek, the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Croatia and, finally, at the European Court of Human Rights. However, justice for Madina has not been served to this day. Those responsible for her death have not been identified nor punished.

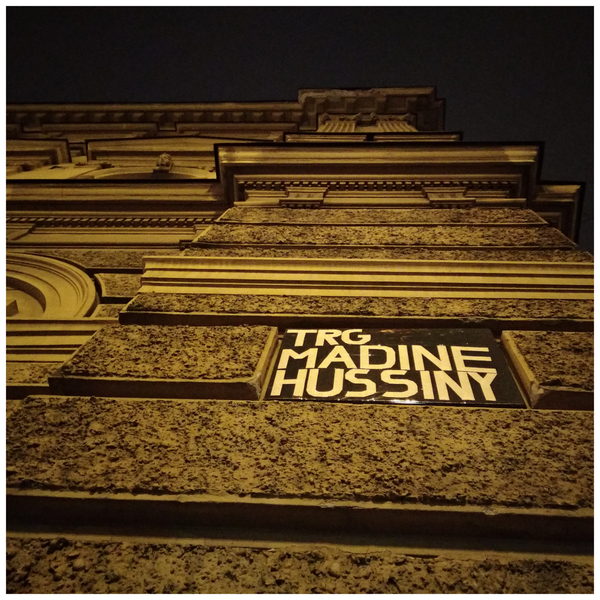

Madina has become a symbol of harsh migrant routes going through Croatia and neighbouring countries, a symbol of border deaths, but also of resistance to policies that imply and produce such deaths. The first anniversary of Madina’s death was marked by the renaming of Republic of Croatia Square in Zagreb to Madina Hussiny Square. This action, as well as other counter-memorialization actions in the following years, was aimed at determining who is responsible for Madina’s death and for all those who were persecuted and died at the borders and in the name of borders. The renaming was used to demand, as stated in the leaflets, swift responsibility for the committed act, for the irretrievably lost life and the system that produces such deaths (cf. grief activism). The third anniversary of Madina’s death was commemorated by a giant graphic novel titled Madina by Ena Jurov, exhibited at the Square of the Victims of Fascism in Zagreb, and on the fourth anniversary, the initiative Zagreb City Refuge submitted a request to the city authority and the Committee for Naming Neighborhoods, Streets and Squares of the Zagreb City Assembly to have the name Madina Hussiny included in the pool of names from which public areas for the area of the City of Zagreb are named.

Commemorating the first anniversary of Madina Hussiny’s death. Trg Republike, Zagreb, 21 November 2018 Photo: Initiative for the Madina Hussiny Square

6/4/2022