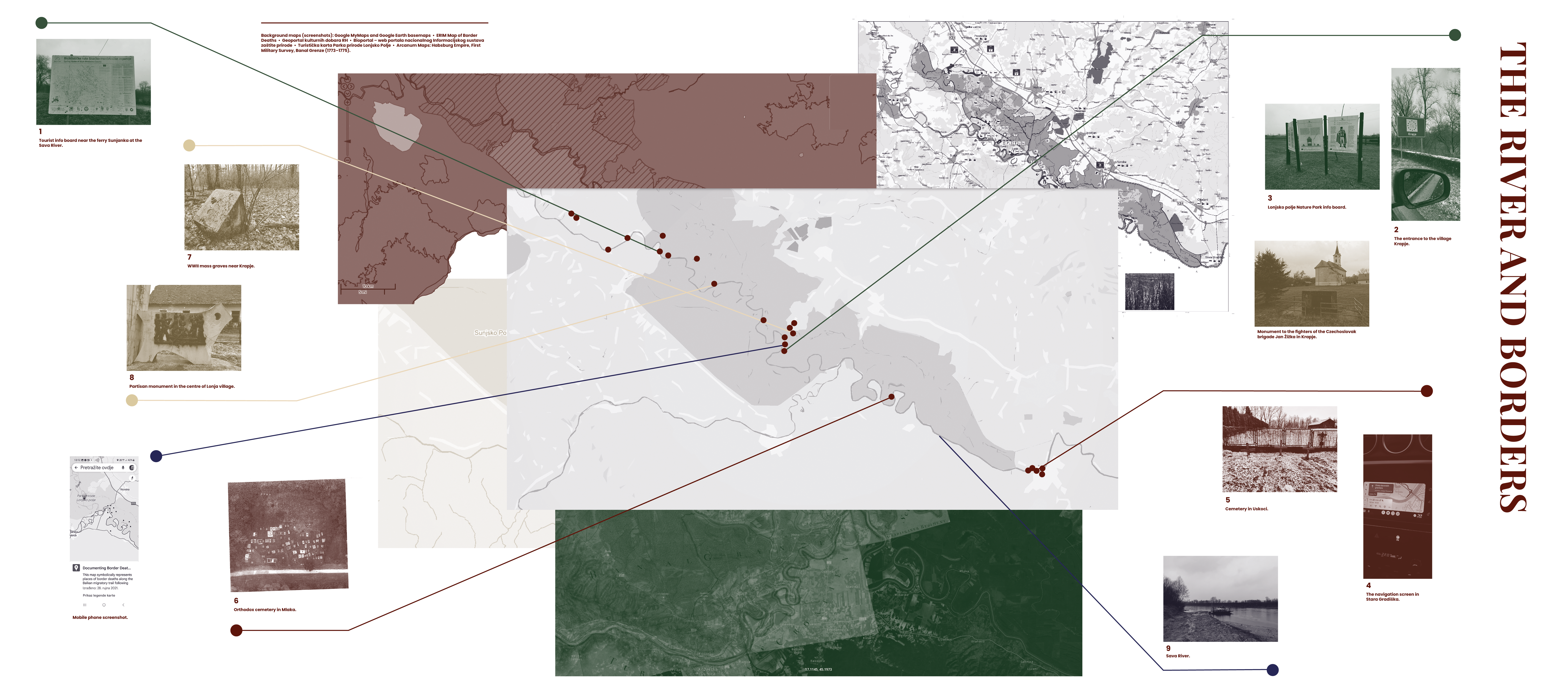

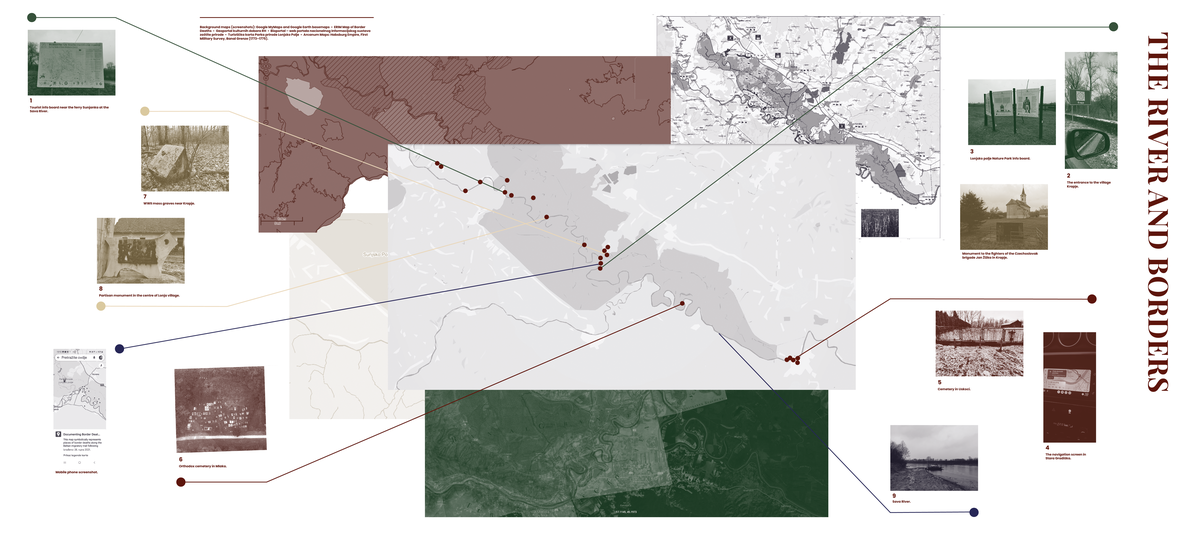

Cartographic Assemblage: The River and Borders

On 14th February 2025, while revisiting several documented border deaths burial sites, we visited the area between Sisak and Stara Gradiška, following the Sava River, toward the Croatia-Bosnia and Herzegovina border—today's external EU and Schengen border. Our field notes, composed of cartographic assemblage as well as written and visual traces, unravel the multitude of coexisting layers which constitute this region. These layers remain invisible in the hypercartographic reality of GIS. They include: dilapidated tourist infrastructure favouring the heritage of the Military Frontier regime; silencing and erasure of human remains and traces of historical and ongoing regimes of oppression, exclusion and violence; the sidelined traces of this region's emancipatory narratives of solidarity and resistance along and across the river's divides. Our notes pinpoint selected locations mapped upon the accumulated cartographic materials we used to navigate this river-border landscape. Fieldwork photos are colour-coded to indicate some thematic connections we identified among them: tourist information signs (green), WWII sites (beige), and sites related to clandestine migration (brown-red).

1 Dilapidated tourist info board for the project Bicycle for Tourism Without Frontiers (BIKE 4 TWF), located by the main road near the ferry Sunjanka at the Sava River.

The map on the info panel shows six roads in Lonjsko Polje Nature Park and their connection to the cycling route leading to Kozara National Park in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The panel informs visitors that the project was developed under the EU IPA Programme for Cross-Border co-operation Croatia—Bosnia and Herzegovina 2007-2013, with a disclaimer: “The content of this info panel does not reflect the positions of the European Union”.

2 The entrance to the village Krapje marked by the logo of the European Heritage Day.

The official European Heritage Days website declares its mission as: “a joint action of the Council of Europe and the European Commission, putting new cultural assets on view and opening up historical buildings normally closed to the public. The cultural events highlight local skills and traditions, architecture and works of art, but the broader aim is to bring citizens together in harmony even though there are differences in cultures and languages.” One of EHD’s aims is to “counter racism and xenophobia and encourage greater tolerance in Europe and beyond the national borders.”

3 Lonjsko polje Nature Park info board at the beginning of The Borderers’ Route (Staza graničara) featuring information about the history of the Military Frontier and a drawing of the graničar with a rifle dressed in military attire.

The panel informs the visitors of the Nature Park: “The Frontier protected Europe from the inroads of would-be conquerors, and at the same time was a cordon-sanitaire guarding the continent from disease. However, it was still open for trade, industry and cultural exchange even if controlled. Dotted along it were fortifications with watchtowers and chardaks sentry posts on stilts [set up in 18th and 19th c.]. But even more than the fortifications, it was protected by the swamps, forests and rivers, which were integrated into military strategy.”

4 The navigation screen shows our way back from the Slavonian Borderers' Coast in Stara Gradiška.

In the opposite direction indicated by the navigation, there is a bridge and border crossing point between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. The queuing of cars and detailed border controls of buses entering the EU are hallmarks of this border-crossing bridge. This bridge was a strategic point during the 1990s war. Largely ineffective UN forces from Nepal were stationed there, and it served as a major escape route for civilians. In recent years, undocumented travelers, refugees, and other migrants have used the new bridge—which has been under construction for years and is located a few kilometers away—for their clandestine crossing.

5 The cemetery in Uskoci, near Stara Gradiška.

Three wooden crosses leaning against the cemetery fence in village Uskoci—each bearing N. N. instead of names—mark the final resting places of three men, migrants who died in an attempt to cross to Croatia, EU. Their bodies were found in or close to the Sava River near Uskoci in 2022 and 2024. The first 2024 finding was made the day after our initial visit to the cemetery in January of the same year. According to local historical records and memory, Uskoci was “founded by refugees from Bosnia in the 18th century, fleeing the Turks—hence the name Uskoci, from uskočiti [to jump in/flee]”.

6 Aerial photograph of the Orthodox cemetery in Mlaka, provided during a visit to the area in 2022.

There are six graves at the Orthodox cemetery in Mlaka, situated at the margins of the graveyard and numbered separately. The oldest grave dates to 2019 and belongs to an unidentified man found in the Sava River. Three graves hold the remains of unidentified men recovered from the Sava River in March 2021. Bones found in the area in 2023 were interred alongside them. In summer 2024, another unidentified man who drowned in the Sava River was also buried there. In times of flooding, like during our last visit to the area, Mlaka and the cemetery in Mlaka cannot be accessed by road. During the Second World War, the Ustasha from the nearby concentration camp Jasenovac killed or forcibly displaced almost all residents from Mlaka, predominantly Orthodox Serbs. Many of them were interned and killed or died as far as Norway, in German forced labour camps. Because of this, Mlaka and the nearby village of Jablanac are sometimes called “disappeared villages”.

7 Location of mass graves at Camp I Krapje, the first camp established in 1941 within the Ustasha Jasenovacconcentration camp system.

Mass graves were documented and commemorated with memorial plaques and a monument in 1967. In the 1990s, the concrete sculpture was demolished and the plaques went missing. Despite its formal protection as a cultural property of the Republic of Croatia (Z-7329), the site has remained demolished ever since and has been completely neglected. The area is currently used for extracting wood from the forest, with horse dung scattered across the mass graves. When we inquired with the Conservation office about responsibility for the mass grave and memorial's condition, their response revealed legal and administrative contradictions designed to shift responsibility and shield heritage institutions from accountability.

8 Monument in the park next to the Catholic church in the centre of Lonja village.

Compared to many other Partisan monuments in the area, this one is in relatively good condition. Designed by the sculptor Nikola Kečanin, it was unveiled in 1964. The monument features a relief depicting an unusual historical scene: crossing a river in boats and transporting supplies. Part of the text on the monument reads: “During the People’s Liberation Struggle, communists and patriots of Posavina built an ‘invisible’ bridge across the river, connecting Slavonian partisans with partisans of Bosnia, Banija, Lika and Kordun, and strengthening brotherhood and unity.”

9 The Sava River is the longest river in Croatia.

It flows through Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia. The Sava River is also a border between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina along certain stretches. In the early 2000s, dozens of people in transit lost their lives while attempting to cross it clandestinely. In recent years, people have once again attempted crossing the river, resulting in the loss of numerous lives, dozens of graves along the riverbanks, and countless disappearances.

8/12/2025